Herrero becomes airborne at Ballaugh Bridge on his way to third place at the 1969 Isle Of Man 250cc Lightweight TT on the monocoque Ossa.

The 2017 MotoGP season once again saw Spanish riders dominating the Grand Prix grid. Ten of the regular twenty-four racers were Spanish, and for the past six consecutive seasons, a Spaniard has won the MotoGP World Championship. The junior Grand Prix classes of Moto2 and Moto3 also have a healthy representation of Spanish talent, and it’s also a Spanish company, Dorna Sports, who hold the commercial rights and play a major role in shaping the series. So it comes as no surprise that the popularity of the sport is so high that four of the eighteen races are held in that country.

Although Salvador Canellas won Spain’s first Grand Prix victory in 1968 contesting the 125cc class at the Spanish Grand Prix, it was a 17 year Angel Nieto who competed in his first Grand Prix in 1964 in the 50cc class that would spearhead Spain’s assault on the World Championships. It was the beginning of a stellar career, one that ended with Nieto reaching an elite level with 13 World Championships., six in the 50cc class and seven in the 125cc class, a figure only bettered by the great Giacomo Agostini with 15 World Championships.

However, it was a rider by the name of Santiago Herrero that looked most likely to win Spain’s first World Championship. Born in Madrid on May 2nd, 1942, Santiago bought his first motorcycle at the age of twelve and in 1962 obtained a racing licence. Initially competing on a Derbi Gran Sport and acting as his own mechanic, Herero then started racing a 125cc Bultaco Tralla. This brought him to the attention of Luis Bejarano the founder and owner of Spanish brand Lube motorcycles.

Bejarano offered Santiago a position in his competition department and in 1964 Herrero repaid that confidence by finishing in third place on a Lube Renn in the Spanish 125cc Championship and then backed up the result with a second place in 1965. Difficult financial times under Franco’s reign saw the Lube marque go out of business. Santiago decided to work for himself and opened a motorcycle repair shop in Bilbao.

Herrero continued to compete as a privateer racing the Lube Renn a Bultaco Tralla and TSS in national events. At the end of 1966, he was approached by another Spanish manufacturer Ossa. Founded by Manuel Giro the company had survived the difficult times of the early 1960s and thanks to the engineering genius of Manuel’s son, Eduardo, the company had developed road racing aspirations having already tasted success in endurance events.

Some early shakedown runs on the monocoque Ossa. Note the Telesco forks and front brake from the 230cc Sport.

It was the dream of winning the 250cc World Championship that inspired Eduardo to start design studies for a new Grand Prix challenger in 1966, and he even considered taking on Yamaha’s RD05 with his own two-stroke V4, but the cost was beyond the budget at his disposal.

The answer was to build a simpler solution using the proven philosophy of lightweight, a small frontal area and engine reliability combined with outstanding handling. Following company ideology, the engine would be a single cylinder two-stroke of 249cc with a bore and stroke of 70x65mm. But unlike the piston port road models, a more accurate rotary disc valve was used for induction, which was fed by a massive 42mm Amal carburettor. An equally enormous expansion chamber exited on the left side of the engine, and a beefy air-cooled seven-fin barrel and cylinder head gave the illusion of a much bigger engine. Ignition was by an electronic Motoplat unit while the gearbox used six gears and was engaged by a dry clutch.

But it was the chassis that moved away from convention. Unique for the era was its welded monocoque construction of magnesium and aluminium sheets that incorporated the fuel tank. The engine was mounted from a lug welded behind the steering head to another lug cast into the cylinder head, the chassis then swooped down and attached to the rear of the crankcases and incorporated the pivot point for the chrome molybdenum steel swingarm. Initially, oleo-pneumatic shock absorbers were used with proprietary Telesco front forks while the front brake of the road going 230cc Sport model was utilised.

The 97.5kg racer produced 42bhp at 11,000rpm and boasted strong torque from as low as 6,500rpm. Nonetheless, it still gave away over 20hp to the Yamaha V4’s.

The innovative Grand Prix racer had its first trial by fire at the 1967 Spanish Grand Prix at Montjuich Park and was ridden by Ossa factory rider Carlos Giro. Although sixth place was encouraging, Giro was a lap down to Phil Read on the Yamaha V4. Eduardo knew that on a tight circuit that should have suited the Ossa, they really needed to be further towards the front.

Meanwhile, Herrero continued to help with development work on the G.P. racer while contesting the 250cc National Spanish Championship eventually becoming the 1967 Champion. However, politics were about to come into play with the Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme issuing new regulations, which would limit the number of cylinders, gears and minimum weight for the different capacity classes from the 1969 season. The governing body of motorcycle sport was attempting to curb the costly technology war that was being waged between the Japanese factory teams and level the playing field for the European manufacturers.

Honda withdrew after the 1967 season followed by Suzuki although Yamaha continued on with factory team until the end of the 1968 season. This would give Ossa a better chance of Grand Prix glory although they still had to deal with the V4’s of Read and Ivy during the 1968 season.

The first Grand Prix of the year was the German round at the Nurburgring, a high-speed circuit more suited to the Yamaha V4 of Ivy and Read. Herrero, though, managed a creditable sixth place a lap down. Next was the Spanish round at Montjuich Park where Herrero qualified 5thand actually led the race but was let down by the oleo-pneumatic rear shocks that failed causing him to crash on lap 8. These were discarded and eventually replaced with British Girling shock absorbers. Some consolation was found for Ossa though, with their second-string rider Carlos Giro coming home in fourth position.

Next was the TT at the Isle of Man with Herrero finishing in a commendable 7thplace for his first time at the island, with Ivy taking the win and Santiago named as the top rookie for the class. Ossa, however, tasted victory for the first time at the TT in the 250cc production race. English Ossa importer Eric Houseley had entered a 230cc Sport for Trevor Burgess in the event, who rode it to victory over the demanding 60.7Km (37.73 miles) mountain course.

Herrero scored another 6thplace at the Dutch TT at Assen, which was again won by Ivy on the V4 Yamaha, and followed this up with a 5thplace at the hi-speed Spa-Francorchamps circuit in Belgium. Herrero, unfortunately, suffered a DNF at the next round at the Sachsenring in East Germany and also missed the next three Grand Prix’, but returned for the final race of the season, the Nations Grand Prix at Monza in Italy. Herrero claimed an outstanding 3rdplace on another high-speed circuit, which was won by Read ahead of Ivy on their V4’s. Read pipped Ivy to the World Championship with Herrero a credible 7th place. Ossa also secured a well deserved fourth place in the Constructors World Championship.

Development of the Ossa racer continued and by now sported Italian Ceriano front forks and four leading shoe front brake with British Girling shock absorbers at the rear. This increased the weight of the machine from 97.5kg to 99.6kg but the improved handling and braking more than made up for the additional weight.

Although Yamaha withdrew works entries for the 1969 season they had been developing the parallel twin cylinder TD2 two-stroke production racer that was made available to privateers. Dutch Yamaha importer, Yamaha NV entered the talented duo of Rod Gould and Kent Anderson on TD2’s. The East German MZ factory was also a threat with their fast but fragile rotary disc valve two-stroke twins, while the Italian Benelli factory had their works four-cylinder four-stroke racers to compete with, in a last-gasp chance to win the title before the rollout of the new regulations made them redundant for the 1970 season. The pundits favourite for the championship that season was Benelli’s Renzo Pasolini who had won seven races in the Italian season openers. This would in no way be an easy campaign for Herrero and the Ossa.

The first race of the 1969 season was the Spanish round held for the first time on the tight and twisty Jarama circuit near Madrid. In wet and drizzly conditions, and much to the delight of the partisan crowd, Herrero won his and Ossa’s first Grand Prix. It was Spain’s first win in the 250cc class – Herrero becoming only the second Spaniard to win a Grand Prix. Sweden’s Kent Anderson finished second on his importer supported Yamaha twin nearly 25 seconds behind.

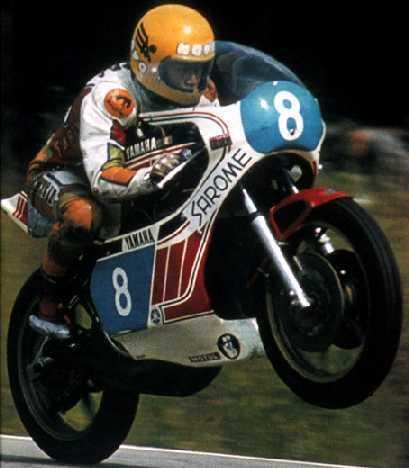

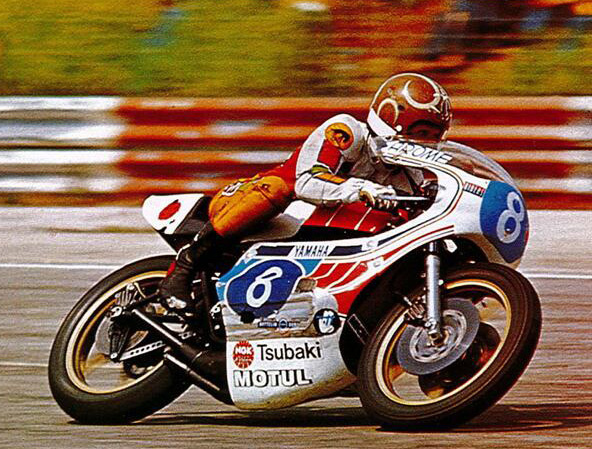

Next was at the West German Grand Prix at Hockenheim. Pasolini, unfortunately, suffered a crash in practice, which was severe enough to put him out for three Grand Prix’. Kent Anderson went on to notch up the first win for the TD2 while Herrero suffered a DNF with ignition failure. Santiago bounced back at the French Grand Prix at Le Mans, winning the race and leading home second place man Rodney Gould on his Yamaha twin by nearly 42 seconds with Kent Anderson third. Benelli by now had drafted privateer, Australian Kel Carruthers, and Phil Read into the team for the next round at the Isle of Man. It was Herrero’s second visit to the TT and experience no doubt helped him to an outstanding third place behind Carruthers on the Benelli and Frank Perris on a Suzuki.

Meanwhile, the Ossa factory continued development of the 250cc racer by water-cooling the head and block of the engine, which reputedly enabled it to produce 48bhp at 10,500rpm. This version made an appearance at the Dutch TT round; Herrero though chose to stick with his tried and tested air-cooled engine.

Pasolini returned at Assen and duly went on to win the Dutch TT. His new teammate, Kel Carruthers was second with Herrero an excellent third place 26 seconds behind the two works Benelli’s. Up next was the Belgium Grand Prix at the ultra-fast Spa-Francorchamps. Santiago underlined that he was a real contender for the championship, winning by a mere half a second from Rod Gould on his Yamaha but almost ten and a half seconds ahead of Carruthers on the Benelli. In fact, Herrero’s average race speed was faster than second placed man Percy Tait in the 500cc category!

Things were hotting up with Pasolini winning again in East Germany at the Sachsenring with Herrero in second place a mere three-hundredths of a second behind with Rosner on an MZ in third. Czechoslovakia was next at the Brno circuit, and it was here Santiago’s championship campaign began to falter. Herrero’s Ossa suffered engine failure while Pasolini won again with Gould in second and Carruthers in third.

Two weeks later the “continental circus” moved on to Imatra for the Finish Grand Prix. Pasolini had the misfortune to crash again putting himself out for the rest of the season. Herrero, however, could only manage sixth place, but more importantly, Carruthers finished fourth, and Kent Anderson took his second win of the season. The pressure was starting to mount on Ossa’s challenge.

The trip to Northern Ireland for the Ulster Grand Prix at Dundrod must have been a pensive one for Santiago. He knew only the best seven results would count towards championship points and he needed at least one more good finish. It may have been self-imposed pressure to do well in the wet and rainy conditions that caused Herrero to crash, sadly breaking bones in his left hand. Carruthers notched his second win on the Benelli with Kent Anderson on the Yamaha third.

Three weeks later at the Nations Grand Prix at Imola, Herrero, with his hand and forearm in a splint, could only manage fifth place. The championship was slipping away. Yamaha had drafted Phil Read on a factory-supplied twin to help Anderson in his title bid and duly won the race from Carruthers on the Benelli with Anderson in third place.

Only one week later was the final race of the season; the Yugoslavian Grand Prix on the Adriatic street circuit of Opatija. For Herrero to have any chance to take the championship it had to be a win or nothing and poor results for his adversaries. Unluckily it ended with another crash for Santiago. To help Carruthers in his title bid Italian rider, Gilberto Parlotti was brought into the Benelli team. It would prove to be a masterstroke as Carruthers won the race followed home by Parlotti with Anderson in third. The final tally on adjusted Championship points was Carruthers, in first place on 89, Anderson, in second place on 84, and Herrero, in third place on 83. Ossa also claimed third place in the Constructors Championship.

Nonetheless, 1969 was a season of accomplishment for Herrero and Ossa. Santiago had won his third consecutive 250cc Spanish National Championship. He had also been drafted into the Spanish Derbi team in the 50cc class of the World Championship finishing 7th in Holland, 2ndin Belguim and 2ndin East Germany. His results helped his friend Angel Nieto to his first 50cc World Championship and Spanish manufacturer Derbi to their first constructor’s title. Although only entering three 50cc Grand Prix’, Herrero finished 7thin the championship.

Herrero and Ossa entered into the 1970 season with a certain amount of optimism. Pasolini and Benelli would concentrate on the 350cc class due to the regulation changes that only allowed machinery with a maximum of two cylinders to compete in the 250cc category. Santiago still faced stiff competition from an armada of private, dealer and importer supported Yamaha’s and MZ could still be a threat, even though the OSSA was by now making 45bhp in air-cooled form.

Herrero’s season got off to a shaky start with mechanical problems causing his retirement from the West German Grand Prix at the torturous Nurburgring. Santiago then put in one of the rides of his life in the French Grand Prix at Le Mans. Herrero crashed while pushing too hard to try and make up for the speed differential between the Ossa and the Yamaha’s. He remounted his battered machine and in a superhuman effort fought his way up to second place setting the fastest lap of the race. Next was the Adriatica Grand Prix at the Yugoslavian seaside town of Opatija. Santiago once again proved he had the makings of a World Champion winning the race by four seconds from Kent Anderson with Rod Gould in third. Herrero led the Championship by two points as the “continental circus” headed once more to the Isle of Man.

Although Yamaha’s TD2 had proven fragile at the TT the previous year, a season of development and the sheer number of competitors racing them put the odds against success for Herrero and the Ossa. In the early stages of the race he could only manage fifth place and while pushing too hard took the slip road at Braddan Bridge. Santiago dropped the bike breaking the screen. He restarted and by the last lap had clawed his way up to third place. As Herrero tried to take the fast but difficult double left-hander at the thirteenth milestone before Kirkmicheal, a section of melted tar put the OSSA into a wobble and a slide that he was unable to recover. Stanley Woods was following Herrero and witnessed the accident before becoming entangled himself trying to avoid man and machine, ending up with a broken ankle, leg and collarbone.

Santiago suffered severe head and internal injuries and was airlifted to Douglas but passed away two days later. Manuel and his son Eduardo withdrew Ossa from racing; his death had devastated the factory. The impact of his accident saw Spanish riders and the Spanish Federation, the RFME, boycott the TT for twenty years. Spain had lost one of its pioneer’s of Grand Prix racing and an outstanding developmental rider. Few would disagree that Herrero could have one day been a World Champion.

Word Geoff Dawes © 2018 Images courtesy http://www.alcherton.com, http://www.progress-is-fineblogspot.com.au, and http://www.pilotes-muertos.com