The ascendency of the Japanese factories in Grand Prix motorcycle racing during the 1960’s brought with it a technical revolution that escalated at a breathtaking pace. The battle for supremacy in the different capacity classes between the advanced two-stroke racers from Yamaha and Suzuki to take on the might of the multi-cylinder four-stroke Honda’s forced the governing body of Grand Prix racing, the Federation Internationale de Motocyclisme, to act. 1969 saw new regulations that placed a restriction on the number of cylinders and gearbox ratio’s allowed as well as a new minimum weight for the different capacity classes. The aim was to enable European manufacturers to remain competitive by reducing the cost of developing new Grand Prix machinery.

Unfortunately, it saw an exodus by the Japanese works teams from the World Championships heralding in a new decade of the privateer, with Yamaha and Suzuki providing reasonably priced production racers to individuals and dealer teams, while their European importers received the latest factory versions. To a certain extent, it levelled the Grand Prix racing playing field; a good privateer could develop their production racer to be competitive against even the factory-supported teams.

However, what is uncommon for this period is a privately built racer to be adopted by a Japanese factory through its European arm and used to win a World Championship. The story of the “Sankito” (an amalgam of the Japanese words for three and cylinder) used by Takazumi Katayama to win the 1977 350cc World Championship is indeed an unusual one.

The origins of the Yamaha triple lay with Swiss sidecar racer Rudi Kurth, an innovative and talented engineer. Kurth had built a 500cc three-cylinder engine based on the twin cylinder Yamaha TD3 by having special crankcases cast that would accept an extra cylinder. Built specifically for sidecar racing, it proved, in 1976 form, that with a bore and stroke of 64mm x 51.8mm and a capacity of 499cc, to be more powerful than the World Championship winning Konig engine. It was also on a par with the hybrid Yamaha TZ 500 four-cylinder engine (TZ 750 crankcase and heads using TZ250cc barrels) but was lighter and more compact.

But although the genesis of the Sankito belonged to Kurth, it was former Yamaha racing mechanic Ferry Brouwer that developed the concept to the point that Yamaha Motor in the Netherlands adopted it as an official project.

Brouwer had been the race mechanic and friend to rising star Jarno Saarinen. But after Saarinen’s tragic death at Monza in the 1973 Nations 250cc Grand Prix, he decided to leave the Yamaha race team and take a job as the head mechanic at a new motorcycle dealership in Amersfoort Holland called Ton van Heugthen Motors. Ton was a successful sidecar motocross racer, and besides developing an XS 650 Yamaha powered outfit for his boss, with which he won the European Championship, Brouwer was also given the freedom to set up a road racing team to compete in mainly Dutch road racing events with Kees van der Kruijis as there rider.

During his years at Yamaha Ferry had developed an extremely close relationship with Minoru Tanaka who had run the factory race team. When Tanaka heard of Brouwer’s plans to set up the Ton van Heugten Racing Team running 250 and 350 Yamaha’s, he spontaneously offered some help by supplying spare parts and tuning data. Tanaka later mentioned that he had been in contact with Rudi Kurth and suggested that they visit him in Biel, Switzerland. Tanaka’s idea was to see if Kurth could make some crankcases, cylinders and cylinder heads for Yamaha so that T.v.H. Racing Team could build a 500cc three-cylinder solo racer.

After receiving the parts, Brouwer built up the 500cc triple using standard Yamaha components. The bore and stroke were 64mm x 51.5mm giving an engine displacement of 496.7cc. The only non-standard piece of hardware was a German Krober ignition, and Brouwer even used a modified TZ frame for the chassis.

While working on the 500cc triple one night, Brouwer came up with the idea of building a 350cc triple. By using the standard 54mm cylinders bore of the TZ 250cc machine and the splined crankshaft of the TD2 that had a stroke of 50mm, it created a capacity of 343.3cc with the added benefit that the individual crankshafts could be set at a 120 degrees firing order. Ferry rang Tanaka who organised the TD2 crankshafts, which Yamaha in Japan still had in stock and within a week work began on the 350cc triple.

The first race meeting for the 350cc triple was a Dutch Championship round at Mill. Although proving to be fast, the triple was also unreliable as the crankshaft was causing problems. Brouwer suggested to Tanaka that they ask Hoeckle in Germany to make crankshafts for the 350 and 500 triples. Hoeckle crankshafts were being used successfully on TZ250 and 350 Yamaha’s, and it would also give them the chance to increase engine capacity slightly. With the new crankshaft, it enlarged the stroke from 50mm to 50.5mm taking the capacity from 343.3cc to 346.79cc with significantly improved reliability.

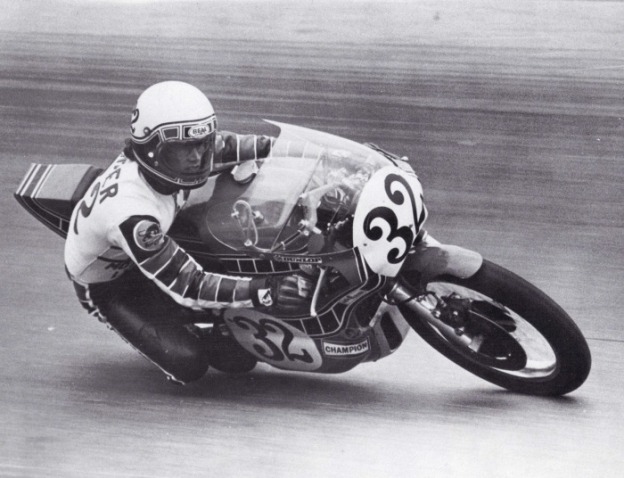

Meanwhile, Van der Kruijis was having success winning several international races and the Dutch 250cc Championship on a TZ250cc Yamaha as well as finishing 5th in the 500cc class behind the likes of Wil Hartog, Boet van Dulmen and Jack Middleburg on the 500 triple. This success prompted Tanaka to enter the 350cc triple in the World Championship for 1977. The “Sankito” now was an official Yamaha Motor NV project and put in the care of 1973 and 1974 125cc World Champion, Swede, Kent Anderson who would with Trevor Tilbury develop the machine.

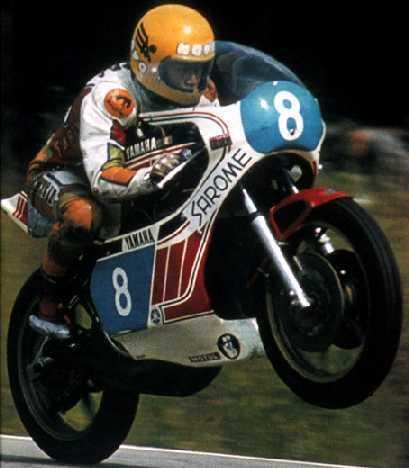

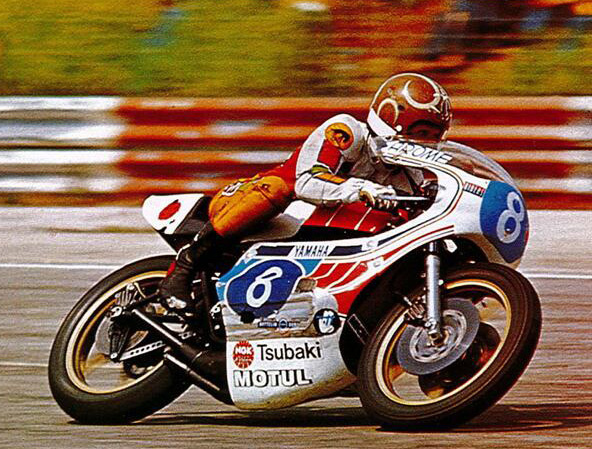

Hard-charging Japanese, Takazumi Katayama and the legendary Giacomo Agostini were named as the riders for the 1977 season. Brouwer and his team would carry on developing the 500cc version building an entirely new machine with a strengthened clutch by adding two plates and larger diameter carburettors and different port timing that boosted power output to 98bhp at the rear wheel. Nico Bakker supplied the frame, and the new 500 became a real threat to the RG500 Suzuki’s.

Bakker also supplied frames for the official “Sankito” 350cc project although a standard TZ frame would also be available. At the same time, Spondon Engineering in the UK was asked to build a chassis as well. Brouwer and his fellow mechanics, Jerry van der Heiden and Melvyn Frey continued to develop the 500cc triple trying out ideas that would help improve the official “Sankito” project. The T.v.H. Racing Team still had a workshop to run and could only work on the race bikes in the evenings and weekends. Their hard work though resulted in a 3rd place for Kees van der Kruijis on the 500 in the 1977 Dutch Championship behind Grand Prix regulars Will Hartog and Boet van Dulmen.

But it was the 350cc “Sankito” that would prove to be a world-beater. By now the triple was producing approximately 15bhp more than the TZ twin, and on a rainy March weekend it was entered in a Dutch national meeting at Tilburg and immediately set the fastest practice lap. Race day dawned with pouring rain, so Katayama elected to use his TZ 350cc twin as the ‘Sankito” had revealed some handling issues in practice. The TZ 350 twin did the job, and Katayama notched up the win. The next outing for the triple was in April at Mettet in Belguim, and its performance was sensational. With no 350cc class to compete in Katayama ran the machine in the 500cc class. On the first lap, the engine would not fire cleanly putting Katayama in18th place before the motor came on full song. By the end of the race, he had passed numerous RG500cc Suzuki’s to take third place while closing in on the leaders.

Meanwhile, the World Championship had kicked off in Venezuela without either Katayama or Agostini. It was left up to Venezuelan, Johnny Ceccetto, Yamaha’s 1975 350cc World Champion, to represent the Yamaha factory, which he did in style with a decisive win riding the TZ350cc twin. The second round of the championship was in Austria at the Salzburgring, and things did not go well, with Katayama crashing the “Sankito” in Friday practice necessitating a significant rebuild for Saturday’s qualifying. Katayama could only manage 3rd on the grid but an unfortunate accident during the race, including one fatality and Ceccotto breaking his arm, saw the race abandoned with no points awarded.

Next in the World Championship was the West German Grand Prix at Hockenheim and the result vindicated Brouwer and Tanaka’s belief in the “Sankito”. Both Katayama and Agostini were entered on the 350cc triple, but it was Katayama that romped away to win by over 15 seconds from Agostini. “Ago” had got a poor start, but in fighting his way up to second place, he had also set a new lap record. Katayama had used the standard TZ chassis but felt its weight and the bulkier engine was detracting from even more potential performance.

At this point Agostini decided to concentrate his efforts on the Yamaha TZ350cc twin and Katayama also used the twin for the next round at the Italian Grand Prix at Imola, picking up a third place podium. The TZ350cc twin was proving more suited to handle the tighter sections at some circuits. Next came Jarama in Spain and another 3rd place for Katayama on the TZ350cc twin. The sixth round of the championship was the high-speed circuit of Paul Ricard for the French Grand Prix. As if to underline the potential of the triple, Katayama won the Grand Prix by over 24 seconds and also set a new lap record. This “Sankito” used the Spondon chassis although Katayama still was not happy with the handling.

When the chassis was destroyed in a fiery crash at a race meeting at Chimay in Belgium the Nico Bakker monoshock was put into service for the rest of the season. Katayama had broken his collarbone in the accident, but it did not hold him back from winning the Yugoslavian Grand Prix at the Adriatic coastal town of Opatija. Coming from behind on TZ350cc twin he set the first 100mph lap of the circuit and established a 30-point lead in the championship.

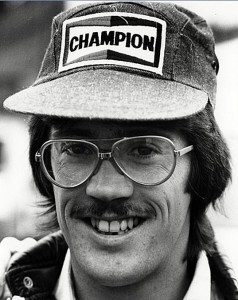

Katayama suffered his first DNF of the season with a broken gear lever at the Dutch TT at Assen after fighting his way up to fourth, again on the TZ350cc twin. The points gap now narrowed to 18 over title rival Michel Rougerie who finished second. The Finnish Grand Prix at Imatra was next on the calendar, a track well suited to the “Sankito” triple. Despite a mediocre start in damp conditions and on slick tyres, Katayama would not be denied, winning by over 3 seconds and taking the 350cc World Championship title. Known affectionately in the paddock as “Zooming Taxi”, Takazumi Katayama became first Japanese to win a World Championship. Of the eight rounds, he contested he claimed five 350cc Grand Prix victories two third place podiums and a DNF. Three of his five victories were on the adopted “Sankito” and two on the official TZ350cc twin. In fact, apart from the abandoned 350cc Austrian race, the “Sankito” won every Grand Prix it was entered in.

Politics at Yamaha Japan now started to play out, as the factory was not interested in developing the 350cc triple. Their primary focus was the TZ twin cylinder racers whose bloodline could be traced back to the road going models the company sold. The “Sankito” once again became a mainly private project for 1978. Separate cylinders were cast to replace the one-piece block of the previous year and Lectron carburettors, as well as a White Power monoshock, were used. It also had the expansion chambers reversed with two exiting on the right and one on the left.

This last version of the “Sankito” was shipped to Venezuela for the first 350cc Grand Prix of the 1978 season for Katayama to use but problems with the machine saw him revert to the TZ 350cc twin to win the first race of the season in his title defence. At this point, the “Sankito” project was abandoned, as Yamaha Japan had no real interest in developing this unique triple any further.

Words © Geoff Dawes 2017. Images courtesy of http://www.cml.blogs.editions-lva.fr, http://www.icpbrasil.wordpress.com, http://www.vk.com