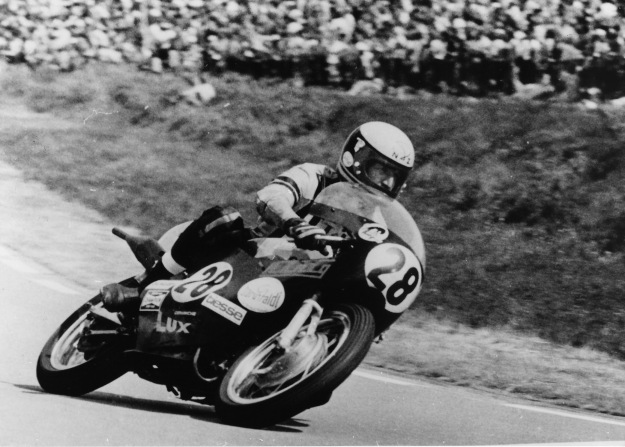

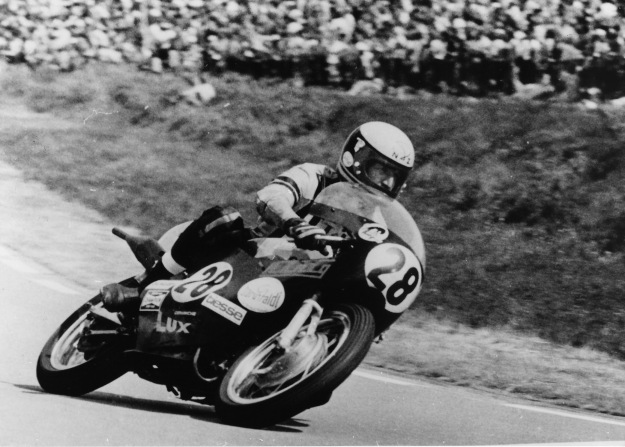

Newcombe in full flight at the Dutch T.T. at Assen.

Before the start of the 1973 500cc Grand Prix season, the all-conquering MV Agusta team held a crushing stranglehold on the premier class. The monopoly had lasted for 17 years, winning the championship 16 times, the last seven in the hands of the great Giacomo Agostini. Even the might of the Honda factory with the talents of Mike Hailwood had failed to take the title away.

In 1973 it was Yamaha who decided to take up the challenge and try to become the first Japanese factory to win the blue riband class. Yamaha’s line up was a formidable one utilising the talents of their 250cc world champion, rising Finnish star Jarno Saarinen, aboard the factory’s latest weapon; an across the frame 500cc four-cylinder two-stroke. His team-mate was respected Japanese test rider, Hideo Kanaya.

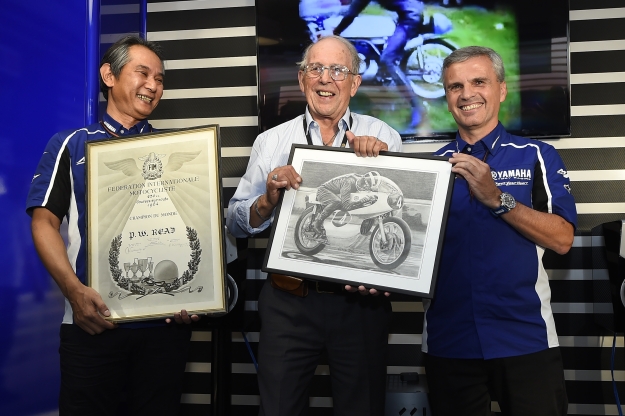

The Italians though, proved they were not about to rest on their laurels by hurriedly building a new four-stroke 500 based on their compact 350 four. Three times 250cc World Champion, Englishman Phil Read, was drafted into the team to ride it alongside Ago on his tried and proven triple.

But incredibly it became an unknown New Zealander, riding a home built special with an engine from a marine outboard motor, that was to be MV Agusta’s greatest threat.

Kim Newcombe was born in Nelson on New Zealand’s South Island but was brought up in Auckland where he served an apprenticeship as a motorcycle mechanic.

Like many great riders of the modern Grand Prix era, Kim’s early racing career was on dirt tracks. His passion, in particular, was motorcycle scrambling (Motocross)), even riding his Greeves scrambler to meetings when a lift wasn’t available.

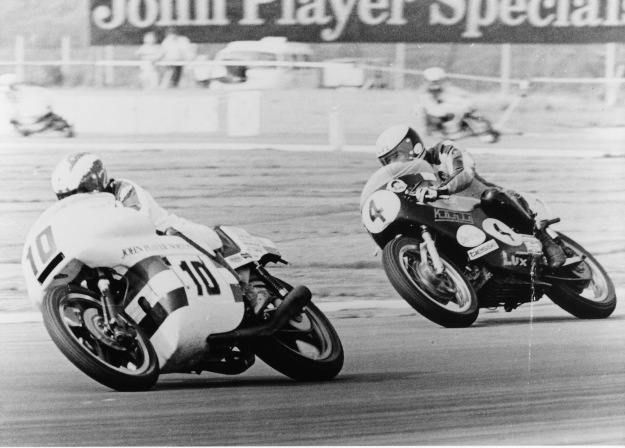

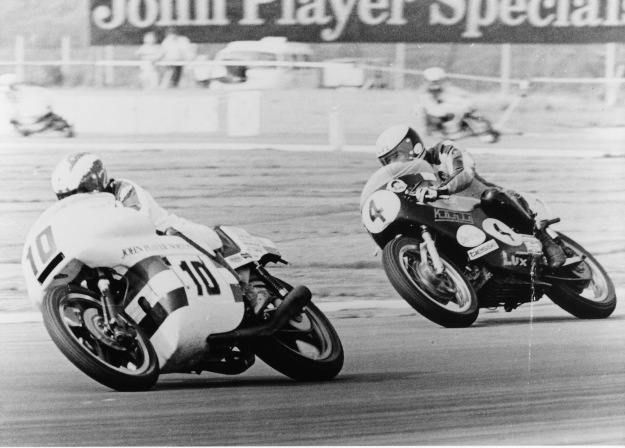

Phil Read leads Newcombe at the 1973 Czechoslovakian Grand Prix.

In May 1962 he was rewarded with a second place in the New Zealand Scramble Championship, which he followed up later that year with another second place in the North Island 250cc Championship. After such encouraging results, Kim and his wife Janeen decided to sell the Greeves and move to Australia in 1963 for what would become a five-year stay.

Newcombe initially spent time in Brisbane where he raced in both scrambles and Speedway. Kim and Janeen then moved to Melbourne, and after putting in some good rides on a home-built special (an outdated Greeves with a BSA gearbox), he received sponsorship from Bob Beanam of Modak Motorcycles in the form of a 400cc Maico. Beanam also sponsored another rider by the name of Rod Tingate, and it was this pair that debuted the first Maico moto-cross bikes in Australia.

However, Newcombe first came across the remarkable German Konig outboard motor while he was working for Bob Jackson Marine in Melbourne. The Konig proved to be almost unbeatable in its class of hydroplane racing, and in 1965 Kim won two Victorian Outboard Championships using the impressive two-stroke engine. In effect, it was these two West German products that would have such a profound influence on Newcombe’s future.

Kim and the Konig lead Read on the MV Agusta at the Swedish Grand Prix in 1973.

Having succumbed to the lure of racing Motocross in Europe, Kim arranged a job as a mechanic with Maico’s experimental department in Germany. But the position was not available until March 1969, and as Newcombe and his wife were to arrive in Europe some eight months earlier something else had to be found. A phone call to Dieter Konig in Berlin secured Kim a job in the Konig factories experimental department, and it was here that the idea of putting the 500cc flat-four two-stroke engine into a motorcycle racing chassis jelled.

Kim found that Dieter Konig was convinced his two-stroke engines could be as successful in Grand Prix motorcycle racing as they were in hydroplane racing and Newcombe was given the resources and encouraged to develop a Grand Prix racer. But it was a German rider named Wolf Braun who had initially shown an interest in racing a Konig, fitting the outboard motor, mated to a Norton gearbox and clutch, in a modified BSA chassis and then giving the hybrid machine it’s first race. But minor injuries and a lack of funds prevented Braun from continuing development of the Konig and the complete bike was left at the factory.

Although Kim was keen to prove his ideas about making the Konig into a competitive Grand Prix racer he had not really considered racing it himself. But towards the end of 1969, Kim decided to race the Konig. In September, after obtaining a West German national racing licence, Newcombe entered his first road race at the Avus autobahn circuit near Berlin and won! The following season saw an entirely new chassis – and Aussie Grand Prix rider John Dodds on the bike.

Again it was relatively short-lived; as a privateer, Dodds could not afford to help develop and race an entirely new machine. Newcombe would again have to ride the Konig himself.

Kim on the Konig at the Dutch T.T. at Assen 1973.

Kim had qualified for an international racing licence for the 1972 season after winning five junior races the previous year. His first international race was at Mettet in Belgium, but it was his performance in the selected Grands Prix which followed that showed Kim and the Konig’s real potential, their best results coming from two third places at the East and West German Grand Prix. The mongrel motorcycle was proving very competitive, with enough power to pass Pagani’s MV on the straights.

Before the ’73 Grand Prix season had started Kim suffered several broken vertebrae in his neck due to a race crash at Hengelo in Holland. This called for a trip to London to see a Harley Street specialist and Newcombe used the opportunity to attend the annual motorcycle show. The main purpose of this was to visit Colin Seeley with reference to making a batch of frames for Konig which Kim had designed himself. By chance, he ran into his old friend and former teammate from Australia, Rod Tingate, who was working for Seeley. Tingate was on the verge of leaving Seeley to have a shot at racing in the European Grands Prix. Rod became an integral part of Newcombe’s team, racing his Yamaha TR3 when he could get a start, but mainly helping to maintain and develop the Konig.

The first race of the season was the French GP at the Paul Ricard circuit in the south of France. The new Yamaha 500 in the hands of Jarno Saarinen dominated the event, easily beating home Phil Read on his MV, with Kanaya’s Yamaha coming in third. Considering Newcombe was developing a new machine, learning a new circuit and progressing as a rider, fifth place in the race was creditable performance. Agostini however, had fallen while trying to stay with Saarinen.

Yamaha took a one-two win in the freezing rain at the next round, the Austrian GP in Salzburg. Again Saarinen dominated, taking the win, while both Ago and Read failed to finish, leaving Kim to pick up a fine third place some 30 seconds in arrears.

On the Podium with Agostini (2) Read (1) and Kim (3) at Swedish G.P. at Anderstorp.

In the heat at the West German GP at Hockenheim, Saarinen broke the lap record, but unfortunately also his chain. Agostini’s MV again failed leaving Read to take the win. It was a challenging race for Kim who in front of his “home crowd” had mechanical problems and did not finish.

The next race was at Monza in Italy. It was a Grand Prix meeting that became one of the darkest days in motorcycle sport. During the 350 race, Walter Villa’s Benelli had broken an oil line, dumping engine oil onto the exhaust system and track. The Benelli was not black flagged by the organisers, but Villa came into the pits on the second to last lap on his own initiative, only to be sent out again by his mechanics so he could claim fifth spot in the race.

The 250 race was started without an oil warning, and there were no oil flags being shown around the track by the organiser’s to indicate the danger. As the leading bunch hurtled at 210kph into the first corner, the Curva Grande, Renzo Pasolini’s bike went down taking Saarinen with him and sending Kanaya into the hay bales.

The group that was closely following smashed into the debris bringing down another twelve riders. A fire broke out among the hay bales and wrecked bikes causing smoke to obscure the accident. There was also no sign of any flag marshals to warn the riders who were on their second lap. John Dodds somehow managed to avoid the carnage and began running down the track waving his arms to warn the other riders. Dieter Braun was leading the race, and it was only the sight of Dodds that saved him from entering the smoke at around 233kph. Sadly both Pasolini and Saarinen were killed. The 500 race was cancelled, and as a mark of respect, Yamaha withdrew for the rest of the season.

With the TT at the Isle of Man being boycotted by all of the top GP riders for safety reasons, the next race was the Yugoslavian Grand Prix on the dangerous street circuit at the Adriatic seaside resort of Opatija. The question of track safety again came into play when MV Agusta decided to boycott this race meeting as well. Newcombe made the most of the situation by winning the event in fine style, coming home over a minute ahead of second place man Steve Ellis and taking the lead in the Championship by four points.

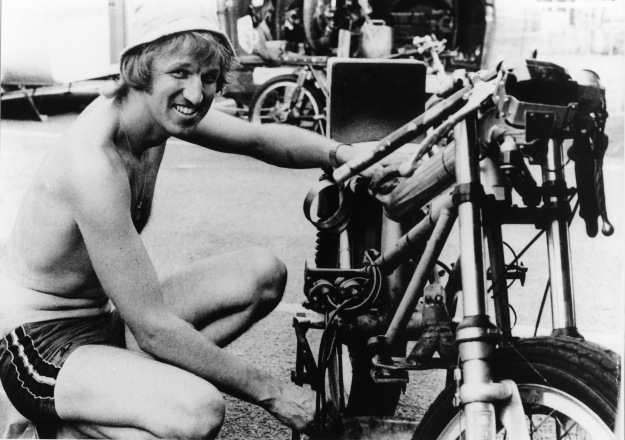

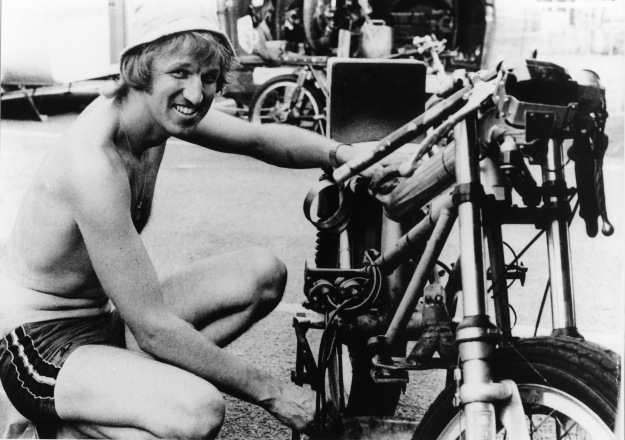

Kim at work in 1973.

The Grand Prix circus then moved on for the Dutch TT at Circuit van Drenthe Assen. Kim was now beginning to experience the pressure of leading the championship in his first full season of GP racing. This showed in practice, causing an uncharacteristic crash on the technically tricky Dutch circuit, and a long night for Kim and Rod to repair the Konig. But on race day, in front of the massive crowd, Kim managed to recover from a poor start and claw his way back through the field to come home in a fighting second place. Agostini, after setting the fastest lap of the race, was out once more with a faulty gear selector. Read again showed his class by taking first place and closing the gap to Newcombe to only one point.

Next was Belgium and the Grand Prix at Spa-Francorchamps, another fast road circuit. Agostini finally broke his duck by winning the race and setting an average lap speed of 206.8kmh, ahead of team-mate Read. Newcombe was holding a safe third place when his water pump drive broke allowing expatriate Aussie Jack Findlay, on the improving TR500 Suzuki, past on the final lap.

Newcombe was now three points in arrears as they travelled once more behind the Iron Curtain to the Brno circuit for the Czechoslovakian GP. Phil Read made a good start and led for half race distance with Ago in tow. Kim was again in third, but his engine was only firing on three cylinders. With just a few laps to go Bruno Kneubler caught up with him, and as they tussled out of the final corner the Konig cut in on all four cylinders spitting Newcombe off! Agostini, however, had managed to get the better of Read and notched up his second successive win.

Newcombe leads Read at the Swedish Grand Prix.

Kim could see his chance at the Championship title slipping away as the Konig team moved on to Scandinavia and the Swedish GP at Anderstorp. If there had been any doubt about Newcombe’s riding ability this race proved his worth. Newcombe took the lead for the first ten laps by pushing the Konig to its limit, using extreme angles of lean through the corners to stay ahead, until he grounded the gear lever which knocked the Konig into neutral and almost sent him spearing off the track. Read was through in a flash to eventually beat Ago by half a second, with Kim in third place.

The Finnish Grand Prix at Imatra was almost disastrous for Newcombe. The bumpy tree-lined circuit was made worse by dirt and damp leaves on the track, causing several excursions up the escape roads with the Konig scrambling for traction in the turns and under brakes. At one point Kim fell as low as eighth but managed to work his way up to fourth at the flag. Agostini had won again, with Read’s second place making him unbeatable in the championship.

There was a break before the final Grand Prix of the season in Spain, the next major meeting being the August 12th “British Grand Prix” international meeting at Silverstone. Kim had ridden the Konig in England for the first time at Brands Hatch the week before, but the poor weather had put a dampener on the meeting, and Kim had no intentions of extending himself while in England.

Bad luck followed Newcombe to Silverstone as he was unable to race the preferred 500cc Konig when in practice it broke a big-end bearing cage. This left the Super Konig, a 680cc version of the bike for competing against the Formula 750 machines in the 1000cc class. The 680 was more challenging to ride being brutally powerful.

Kim on the 680cc Konig chases Peter Williams on the Norton F750 racer at Silverstone.

All the big names were at Silverstone for the 1000cc event. Paul Smart (Kawasaki 750), Barry Sheene (Suzuki 750), Phil Read (MV), Agostini (MV), Gary Nixon (Kawasaki 750), Yvon Du Hamel (Kawasaki 750), Dave Croxford (Norton 750), and Peter Williams (Norton 750) amongst others. But for six laps Newcombe on a hybrid home-built racer proved embarrassingly fast for the factory racers. Smart gradually pegged back the Konig, and as they swept into Stowe corner Kim’s brakes appeared to fade, causing him to run wide and eventually crash. Newcombe and the Konig slid for a distance before smashing into an unprotected brick wall.

Although his injuries appeared superficial, Kim had suffered severe head trauma similar to that of Suzuki’s Kevin Magee’s at Laguna Seca. Unfortunately, the modern medical techniques that saved Kevin’s life were unavailable to Newcombe. Three days later Kim succumbed to his injuries in a Northampton Hospital.

As usual, Newcombe had walked the circuit before practice began, and was involved in a four-hour meeting with race organisers over concerns about safety. It’s ironic that the next day an identical accident occurred at the same corner, yet the rider was able to walk away, thanks to hay bales belatedly being placed there.

Posthumously second in the 1973 500cc World Championship, Kim Newcombe’s achievement should not be overlooked. Taking on the might of the unbeatable MV Agusta team with what amounted to a home-built special on a shoestring budget, and in his first full season of Grand Prix racing, deserves much more than that.

Konig Technical File

The success of the Konig flat-four two-stroke boxer engine design is quite unique in the history of the 500cc Grand Prix class.

Similar layouts were tried later in the mid-seventies. However, Helmet Fath’s more advanced two-stroke design was never as successful in the Grands Prix, and MV Augusta’s boxer four-stroke was never raced.

Kim and the Konig in the paddock at the Swedish Grand Prix. Note the Norton gearbox casing and the belt drive to the water pump and rotary disc valve.

The water-cooled unit sat transversely across the frame with two cylinders pointing forward and the other two rearward. The two right-hand cylinders fired together while the left-hand pair repeated the process 180 degrees later. Basically like two flat-twins sharing a common crankcase and a single crankshaft. The crankcase itself was split into two separate pumping chambers for each pair of opposed cylinders – a necessity for two-stroke breathing.

This enabled the use of a single large rotary disc valve on top of the crankcase for inlet timing, with a single inlet port for each pair of opposed cylinders. The disc valve was driven by a toothed belt from the timing end of the crankshaft, and appeared somewhat fragile, as it had to run through rollers and make a ninety-degree turn.

Even the expansion chambers were shared – initially an agricultural looking single “canister” chamber with the front and rear pairs of cylinders siamesed into it. This was later replaced with two conventional looking expansion chambers – one for each pair of front and rear cylinders.

Carburation varied from two East German BVF carburettors to a twin-choke 38mm downdraught Solex, and finally a pair of American 42mm Tillotsons. The engine ran on petroil at an old-fashioned 16:1, although this was later changed to 20:1 using a vegetable oil.

All the internal components were quality West German products, with the crankshaft being a pressed up five-piece affair made by Hoeckle. It rested on three main bearings – utilising a double ball on the timing end and two separate ball races on the primary side, with split-type caged rollers for the middle main bearing. Caged roller bearings were also used for the connecting rod’s big-end, while the little-end used crowded needle rollers and shims on the piston pin to centralise the conrod. The pistons themselves were forged high silicone Mahle items with a single chromed ring. Bore and stroke were a classic ‘stroker 54x54mm although this was said to have changed during development to 50x56mm.

The ignition system was provided by a conventional battery, twin coil and dual points set-up, run off the right-hand end of the crank.

The main weaknesses with adapting a design intended initially for power boating was the lack of an in-unit clutch/transmission and getting enough water through a cooling system that was built for a limitless supply of cold sea water.

The clutch/gearbox problem was overcome by running a toothed Westinghouse chain off the left-hand side of the crankshaft (hence the reasoning to mount the engine across the frame), to a clutch and a Norton gearbox casing fitted with a Schaftleitner six-speed gear cluster.

The cooling problem was never solved entirely, and the engine did not like to get any hotter than 60 degrees. A cast-finned sump was fitted underneath the engine to act as a reservoir for five litres of coolant that passed through a large radiator. Newcombe experimented with slots in the fairing, which yielded some success, but just in case the Konig was never warmed up before a race so it could be taken to the starting line cold.

Kim hard at work on the Konig at Spa in Belguim.

In its final 1973 form, the Konig had a chassis designed by Kim that used Ceriani front forks and drum brakes with Girling rear shocks. By this time the engine was pumping out 85bhp at 9,800rpm (at the crankshaft) with the 680cc version giving 90bhp to 9,500rpm. With a weight of only 139kg, the 500 was good for around 265kph!

Konig made eight bikes in kit form (less wheels and front forks), and for about the same price as a TZ350 Yamaha, a privateer could buy a potentially competitive 500cc or 680cc racer.

With Kim’s demise though, interest in the solo racer diminished. The factory did, however, help Rolf Steinhausen and passenger Josef Huber in the sidecar championship, for which they were rewarded with a Konig engine winning both the 1975 and 1976 Sidecar World Championship.

Words Geoff Dawes (C) 1991. Photograph’s Mick Wollett, Jan Heese, Robyn’s Liege and Volker Rausch. Published 1993 Bike Australia, Classic Racer (UK) and Extra Editon Motorcyclist (Japan).