At the end of the Second World War former allies, the United States of America and the communist Union of Soviet Socialist Republics entered into a period that was aptly described as “the cold war”. Both superpowers, armed with ideological distrust and a large arsenal of atomic weapons, knew that a direct confrontation would only bring about mutually assured destruction.

Each side fought the other indirectly by trying to influence foreign countries politically and economically while also aspiring to claim global prestige on the high ground of advanced technology – in particular, what became known in the 1960s as the “Space Race”.

It was no doubt a rude shock to America when in 1961 the Soviets put the first man into space to orbit the earth in the spacecraft Vostok 1. Vostok (meaning Orient or East) became a household name around the world and one that was adopted by the communists for a little-known foray into World Championship Grand Prix motorcycle racing.

Although the former eastern block countries of Czechoslovakia and East Germany are better recognised for their motorcycle production and Grand Prix prowess, thanks to CZ, Jawa and MZ, it was in the town of Serpukhov 99km south of Moscow that these not so widely known Russian racers were built.

In 1942 the Central Construction and Experimental Bureau were established in Serpukhov with the aim of providing research and development for the numerous mass production motorcycle factories dotted around the USSR, in a bid to help the Soviet war effort during the Second World War.

At the end of the conflict German motorcycle manufacturer, DKW fell into the hands of the Soviets. In the1930’s DKW had been the largest manufacturer of motorcycles in the world. The Russians plundered the Zschopau factory confiscating its technology and taking it to the Serpukhov Bureau,

Unsurprisingly this spawned blatant copies of the two-stroke DKW racers. The S1B, the S2B and the S3B were all reproductions of pre-war DKW’s with capacities of 125cc, 250cc and 350cc while the “S” (sometimes referred to as “C” which translated from the Russian Cyrillic alphabet stands for “S”) in the acronym stood for the town of Serpukhov.

Motorcycle competition and record-breaking took place post-war in the USSR but there was no participation in international events. The Soviet motorsport governing body the URSS was not affiliated with the Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme (FIM), but by 1954 the communists became interested in competing on the international stage. The Central Automobile and Motor Cycle Club of Moscow joined the FIM two years later on the 1st of January 1956.

But in 1954, in preparation for entry into international road racing, the Serpukhov Bureau designed (believed to be by Evgenij Mathiushin) a new series of four-stroke racers simply designated “S” for Serpukhov. The classification of these racers was quite simple. The S-154 had a 125cc capacity represented by the “1” and “54” was merely the year it was designed.

Its architecture was double overhead camshaft driven by shaft and gears on the right-hand side. The single-cylinder was slightly inclined with a “square” bore and stroke of 54 x 54mm giving a capacity of 123cc and an output of 12.5hp. The chassis resembled a smaller version of the Norton Featherbed frame while the overall weight was approximately 80kgs with a top speed around 140kph.

S-254 was designed as a 250cc twin-cylinder four-stroke racer with the same “square” dimensions of 54 x 54mm as the S-154 and also used double overhead camshafts, this time driven by an inclined shaft on the right-hand side of the engine to the inlet camshaft which in turn on its left-hand end used gears and a pinion to turn the exhaust camshaft. Ignition was by coil while twin carburettors supplied the fuel and final drive was by a five-speed gearbox. Weight was 126kg, and with 23bhp available, at 8,200rpm it boasted a top speed of 150kmh. For the chassis, a Featherbed type frame with earls type front forks was utilised, and initially, it was equipped with a dustbin fairing.

Serpukhov’s 350cc machine was the S-354 and of the same design as the S-254 but with the bore and stroke taken out to 60 x 61mm for 348cc. Power was initially 33bhp at 8,200rpm and with a weight of 144kg was capable of 165kph. It used a duplex cradle frame was best described as a cross between a Manx Norton and a BSA Gold Star design and utilised earls type fork. A “bikini” fairing provided the aerodynamics.

Then came the S-555, a bored-out version of the 350cc S-354 with a bore and stroke of 72 x 61mm giving the short-stroke engine a capacity of 498cc with a claimed power output of 47bhp at 7,400rpm and a top speed of 190kph.

There was also a 175cc machine simply designated the S-175. This was not a bored out S-154 or half of the 350 twin and had a bore and stroke of 64 x 54mm for 174cc. It utilised a vertical cylinder like the later version of S-154, the S-157, and also boasted a twin-plug cylinder head, which became a feature of the S range in 1960. Although it was not an eligible capacity for international racing, a 175cc category was introduced into Soviet national competition.

With no official factory based team running on a permanent basis the Bureau loaned the “S” racers to preferred motorcycle clubs in the major cities. These machines were made accessible to promising road racers as they were well in advance of the out-dated two-strokes and altered road bikes that were available to the majority of competitors in national events.

Although these machines competed with a certain amount of success in race meetings mainly in the USSR, it was the Czechoslovakian manufacturer Jawa that in 1957 appeared to have a Grand Prix machine capable of competing at an international level bringing a halt to the development of the Serpukhov factories middleweight DOHC racers the S-257 and S-358. Czech racer Franta Stastny had ridden a Jawa 250cc racer to 12th place in the 1957 Lightweight TT on the demanding Isle of Man Mountain Course. This brought about a closer collaboration between the Serpukhov Bureau and Jawa. It effectively saw replicas of the Jawa 250cc, and 350cc racers re-badged as S-259 and S-360 Serpukhov machines, although a number of components were made in Russia.

These two “S” racers used twin overhead camshafts driven by a vertical bevel shaft positioned behind the two cylinders, driving the inlet camshaft and a horizontal shaft across the top of the engine to drive the exhaust camshaft. The cylinders were inclined at 10 degrees, and a heavily finned wet sump held the engine oil. The cylinder head sported two valves per cylinder and twin spark plugs with a battery and coil ignition. A pair of Amal carburettors provided the fuel and final drive was via a six-speed gearbox.

The frame for the two racers was conventional tubular construction either diamond or Featherbed with 19-inch wheels. The 248cc version had a bore and stroke of 55 x 52 mm and produced 38bhp at 11,000rpm. With a weight of 128kgs, a top speed of 190 km/h could be reached. It’s thought the 350cc version had a bore and stroke of 62 x 57.6mm and approximately 46bhp 10,300 rpm with a weight of 130kgs. 210 km/h was believed to be the top speed.

The Jawa replicas were a step in the right direction for the Serpukhov Bureau. Russian rider Nikolai Sevostianov on the S-360 claimed third place in May 1961 at the Djurgardslopper international race meeting held at Helsinki in Finland.

It should be noted that the Jawa 350cc “version” did considerably well over the course of the 1961 Grand Prix season with factory riders Franta Statsny and Gustav Havel claiming a double 1st and 2nd places in the German and Swedish Grand Prix’ eventually finishing 2nd and 3rd in the 350cc World Championship

More progress came when the Soviet team made their debut in the World Championships at the East German Grand Prix at the Sachsenring in August 1962. By now the “S” racers were sometimes entered as CKB or on occasion as CKEB in reference to the Central Construction and Experimental Bureau in Serpukhov. Again it was Russian rider Sevostianov that provided the results finishing fifth in the 250cc class and in the 350cc category a fine sixth place.

The team returned in 1963 to the East German Grand Prix taking fifth place for Sevostianov riding the S-360 in the 350cc class. Sevostianov accomplished an even better result at the Finnish G.P. held at the Tampere circuit coming home in fourth in the 350cc category, although there is a side story to this result as the outcome may have been a Podium. The following is the doyen of motorcycle journalists Chris Carter’s recollection of the event published in his book “Chris Carter at Large.”

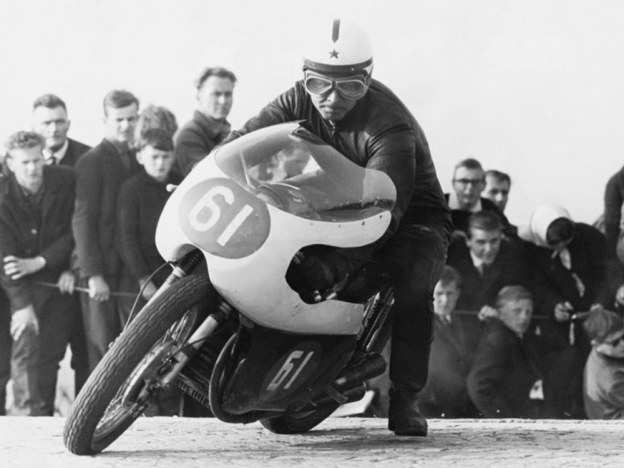

Carter, “Mike Hailwood was there on his 350cc and 500cc MV Agusta’s, and there was a Russian guy on one of these Russian four-cylinder Vostoks (authors note: it was, in fact, a twin-cylinder S-360). Down the straight, he kept looking across at Hailwood, and he wouldn’t brake for the first-right hander until Hailwood did. Hailwood became furious with this man, so in the end, quite deliberately, he didn’t brake at all. They both shot up the slip road, and then Hailwood … put his foot on this man’s petrol tank and shoved. The poor Russian and his Vostok went crashing to the ground.” Hailwood went on to win the race. Sevostianov was also entered in the 500cc class and took sixth place on a bored out S -360 twin.

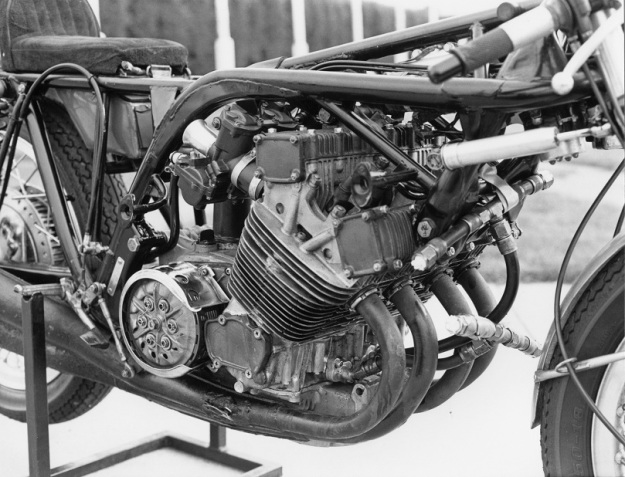

As the results of the “S” racers in the World Championship improved, the head of the Serpukhov Bureau, Ing. Ivanitsky, and the Deputy Director of Laboratories at the Vniimotopram Institute, V Kuznetsov, decided it was time to take on the European and Japanese factories at their own game with a completely new design. The 1964 S-364 was a 350cc four-cylinder four-stroke and the first from the Serpukhov Bureau to be entered as a Vostok. The ambitious project also included a 500cc version to challenge for the blue riband class but was still on the drawing board.

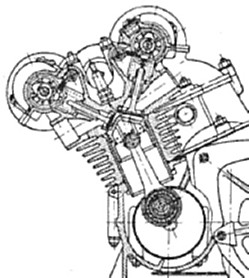

The Vostok’s engine architecture took its design cues from the Italian multi’s and the Honda’s with double overhead camshafts being driven by a central gear train. Bore and stroke were oversquare with dimensions of 49 x 46mm for a capacity of 347cc. Ignition was by magneto and coil while four 30mm carburettors supplied the fuel and the final drive was via a dry clutch and six-speed gearbox. The first Vostoks used the frame and suspension units of the Jawa/CKB racers. Weight was around 130Kgs with a top speed of 230km/h.

It was at the East German Grand Prix in July 1964 that the Vostok S-364 made its international debut, creating a flurry of interest, as these were the most technically advanced Grand Prix racers to come out of the Soviet Union. It was not to be the introduction though that the Serpukhov Bureau would have hoped for as both the entries of Sevostianov and Estonian rider Endel Kiisa retired with mechanical problems after holding third and fourth place behind Jim Redman on a Honda and Gustav Havel on a Jawa. Sevostianov also raced in the 500cc class on a bored-out version of the CKB S-360 twin and managed a fourth-place finish.

In August at the Finnish Grand Prix Endel Kiisa recorded the Surpokhov racers best result in the World Championship so far with a podium third place behind Redman and Beale on Honda’s. But it was not on the Vostok four but the CKB S-360 twin cylinder.

However, the Vostok four did appear again in September at Monza in the Nation’s Grand Prix. Unfortunately, Sevostianov and Kiisa both retired with mechanical problems, which was said to be with the ignition, but in reality, the S-364 was destroying its pistons as it had done on debut in East Germany.

The four-cylinder reappeared again in 1965 at the first round of the championship, the West German Grand Prix at the Nurburgring. The Soviet team arrived a day late and Endel Kiisa could only manage one practice session. On the starting grid for the mandatory push start the Vostok refused to fire, but once he got on his way, Kiisa managed to fight his way through a pack of privateers to finish in fifth place. In a field that included riders of the calibre of Agostini and Hailwood on factory MV Agusta’s, it was a promising result. Only a week later at the non-championship Austrian Grand Prix, he very nearly gave the Vostok its maiden international triumph only to retire a just a kilometre short of victory.

Before the East German Grand Prix later that year significant changes were made to the Vostok S-364. A new frame based on the Norton Featherbed design was employed, and the power unit was improved with a new cylinder head and an oil cooler mounted in front of the engine.

Unfortunately, both Vostoks retired from the East German race, but only a week later, at the Czechoslovakian Grand Prix in Brno, Sevostianov took the honour of a 3rd place podium behind Jim Redman on a works Honda and Derek Woodman on an MZ. It was the best result so far for a Russian rider on a Russian designed and built racer in the classics.

The Vostok did compete at the Nations Grand Prix at Monza in Italy in September with Kiisa finishing in eight spot, and again later that month for a meeting organised by the Automobile Club of Milan as an Italy vs USSR match race series. Italian riders filled the first six places of both races, and sadly this was also the last international event for the Vostok S-364.

There was to be however one last hurrah for the Vostok racers. A 500cc version of the four-cylinder machine had been built with the designation S-565 presumably making it a1965 design although it was based on the 350cc model. With a bore and stroke 55 x 52mm for a capacity of 494cc the engine produced a reputed 80bhp at 12,400 rpm. Weighing in at 155kgs it was good for 250 km/h. There were some minor visual differences to the 350cc version with more fins to the cylinders a deeper sump and more fins on the front of the crankcases.

In 1968 the Vostok team turned up for the Finnish Grand Prix just over the Soviet border at Imatra. With Honda and Mike Hailwwod’s withdrawal from the World Championship, it was assumed the race would be a cakewalk for Agostini and the MV Agusta triple. As expected “Ago” took the lead with Kiisa and the Vostok glued to the back wheel of the MV. Three laps in, and to the amazement of the crowd, the Vostok accelerated past the 500cc World Champions out of a slow corner. This was the first time a Soviet machine had led a 500cc Grand Prix. It was not to last with Kiisa experiencing ignition problems and retiring from the race. Sevostianov saved some face for the Vostok team by finishing in fourth place.

For 1969 some improvements were made to the S-565 Vostok, with a new four-valve head and huge drum brakes fitted that were developed originally for the Jawa V-four 350cc two-stroke.

The upgraded machines were entered in the East German Grand Prix at the Saschenring. It was not to be a good meeting for the Vostoks. During the wet race, Kiisa returned to the pits to change a spark plug finally managing tenth place, while his teammate fellow Estonian Juri Randla had held third place but a misfire and carburettor problems forced him to retire. Seven days later at the Czechoslovakian Grand Prix, both Vostoks retired on the second lap. It was a humiliating conclusion to an endeavour that held so much promise but was defeated by lack of an adequate budget to fully develop these fascinating Grand Prix racers.

Words © Geoff Dawes 2018. Images courtesy http://www.b-cozz.com, http://www.cold-war-racers.com, http://www.fim-live.com, Twitter.