According to the Collins English Dictionary, “instinct” is an inborn intuitive power. It’s also the name of the project that Duncan Harrington undertook in his final year as an Industrial Design student, and from which came the innovative motorcycle you see on these pages. Duncan readily admits that it’s perhaps a misnomer when applied to his well thought out and engineered creation, but it does say something about his own intuition when it comes to questioning the primary and secondary safety of today’s motorcycle designs. But more of that later.

It was at the beginning of the year when 26-year-old Duncan proposed, as just one of his final year’s projects, to produce a motorcycle that would improve upon conventional chassis design and safety. Unfortunately, the powers to be at the Underdale Campus of the University of South Australia needed a fair bit of persuasion, so the first half of the year was taken up with a research paper into roots and origins of motorcycle culture, which Duncan then used to help justify the project. This was followed by a whole range of concept designs that were drawn up and presented before one was finally chosen.

Duncan then had to convince the University that he had the technical skills and know-how to complete the project in the time allowed. Not an easy task with only six months left to do it in. Fortunately, Duncan had completed an apprenticeship as a fitter and turner with CSR Softwoods in his hometown of Mt. Gambier before going to University and also had quite a few years experience restoring cars and motorcycles at home.

There was still, however, one more hurdle – finding the money to pay for the materials and components to construct the bike. A sad farewell was said to Duncan’s bevel drive, square case 750SS Ducati, when it was sold to help finance the project, followed later in the year by his rebuilt Suzuki Katana. Only the time factor remained, and as Duncan succinctly put it to me, ” I haven’t had a holiday all year!”

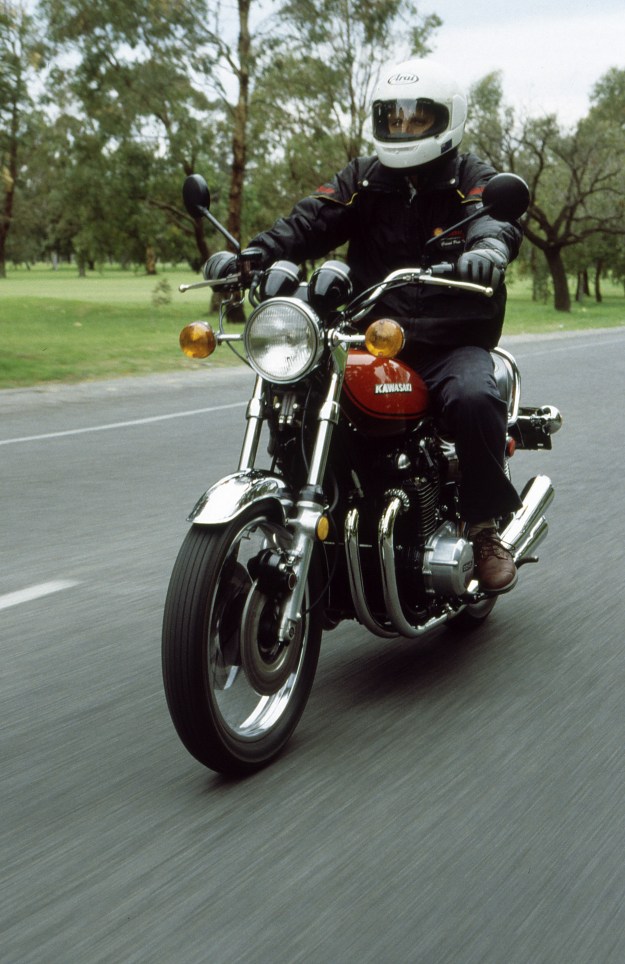

But after watching Duncan work meticulously on “Instinct” and listening to him talk about the ideas that went into the bike, I got the distinct impression that this was more than just a final year project. Which is quite understandable considering a large proportion of the bike had been handmade, polished and painted by Duncan.

The first impression of the bike is its high quality of workmanship, and a feeling of familiarity with its layout – the white chrome-moly steel trellis frame, single-sided swingarm and exhaust exiting under the seat is reminiscent of the Ducati 916. Even the exotic double wishbone front suspension has been tried before on other motorcycles like Kiwi John Britten’s V-twin, and the American Hossack (it’s also been experimented with by expatriate South Aussie Tony Foale who by coincidence is distantly related to Duncan).

The under engine fuel tank is also not new and has appeared on some racing motorcycles in the search for a lower centre of gravity – bikes like the Mead and Tompkinson endurance racer, and the French Elf endurance and 500cc G.P. racers. But perhaps more importantly, it’s the sum of “Instincts” parts and the thinking behind them that makes this motorcycle special – particularly when it comes to selling new ideas to a very conservative bunch of consumers.

For example, the use of a more traditional engine design, in the shape of Honda’s venerable big single NSX 650cc motor, is not just merely to keep costs down. Like most contemporary big singles, the dry-dumped Honda engine is designed to sit high in the frame and “Instinct” utilises this characteristic to enable the fuel tank to be easily mounted underneath it. The chrome-moly trellis frame was another natural choice, as Duncan has designed it to be made in a kit form to suit most big single-cylinder engines that generally have their mounting point at the cylinder head and above or below the gearbox. Just as important though, is that this type of frame offers good mounting points for the front wishbone suspension, and it’s also more visually acceptable in the eyes of purists.

The solid looking front “fork” is also made from chrome-moly steel and is encased in carbon-fibre for added torsional stiffness. This is attached to the two alloy wishbones by a 14mm upper and 16mm lower ball joint that can be adjusted by thread and lock nut to vary the forks rake from a fairly standard 25 degrees to a very steep 18 degrees. The front suspension also makes use of car type polyurethane bushes, while the double wishbones move on plain bearings in order to keep costs down.

The clip-on style handlebars and top yoke pivot in what looks like a conventional steering head (the lower part of which doubles as the top mounting point for the front shock absorber) and uses two rods with eyeball joints at both ends to attach the steering yoke to the fork. The bottom of the front shock absorber is angled out onto a mount at the front of the lower wishbone.

The shock absorber itself is an American car racing A.V.O. unit, with infinitely adjustable rebound and compression damping. Duncan found the A.V.O. shock absorbers specification to be very good, and apart from being a lot cheaper than the “name” brand motorcycle type, it can also be purchased as a single unit with the added bonus of different rate springs being available for a mere $30.

The fuel tank is a carbon fibre, glass fibre and kevlar composite, wrapped around aluminium side panels and inner bulkheads that also act as baffles to stop the 18 litres of fuel sloshing around. A reliable solid state Facet electric pump is mounted down by the petrol tank and takes care of the fuel supply to the carby.

The dummy tank and seat unit are made from injected high-density polystyrene that incorporates aluminium plates for strength at its mounting points and is wrapped in overlapping layers of carbon and glass fibre, again to add strength. The whole thing pivots upwards at the front for good access to the battery, cylinder head and oil tank, although the oil tank cap is also easily accessible even with the dummy tank unit in place.

The seat and dummy fuel tank pivot forward for good access to the battery cylinder head and oil tank.

The seat itself is sculptured from a thin rubber base and covered in vinyl before being glued in place. Another interesting feature of the dummy tank/seat unit is its single rear mounting point. This is directly below the seat and uses urethane bush to help the thinly padded perch absorb some of the road shocks. The paint job is also a local product called Two-pack Pro-Tech polyurethane and is used by HSV on the Commodore.

Duncan also made the stainless steel exhaust system, (apart from two one hundred and eighty-degree bands in the header pipes just after they exit the twin-port head, courtesy of Pace Maker Exhausts) and the aluminium muffler. When viewed from the rear the muffler combines with the seats tail-piece to look uncannily like a snakes head!

As mentioned earlier the bike was designed to be built in a kit form and can use a variety of single cylinder engines, rear suspension, swing arms, wheels and brakes. On Duncan’s prototype, these were cannibalised from a 400cc V-Four Honda NC 30. A special thanks has to go to Alan Rigby Motorcycle Service in Mt. Gambier who supplied the wheels and tyres for just $300, including the cost of sending them to Adelaide.

This brings us to how Duncan Harrington’s design has improved primary and secondary safety over the latest motorcycle designs from the worlds largest manufacturers. Well, not surprisingly, there first came an intensive study of motorcycle design, followed by extensive research into motorcycle accidents, which included material supplied by Adelaide Universities renowned Road Accident Research Unit.

To improve primary safety ,two things had to be accomplished that in general terms are contrary to each other – manoeuvrability and stability, which in most modern motorcycle designs is at best a compromise. Duncan got his design off to a good start in the manoeuvrability stakes with a wheelbase of just 1380mm, helped by a light weight of 140kg with oil but no fuel. This compares well with the likes of Suzuki’s 250cc RGV two-stroke (they also share similar power to weight ratio’s), but where “Instinct” shines is with its lower centre of gravity, thanks to the underslung fuel tank, and also by keeping the centre of mass as close to the middle of the bike as possible.

The other innovation that Duncan’s bike has over conventional designs is the improved stability achieved by taking advantage of mechanical characteristics of a twin-wishbone front suspension. With a conventional telescopic front fork even normal braking will cause them to compress and effectively shorten the wheelbase. Combine this with turning into a corner, which rolls the contact patch across the curved tread away from the centre crown of the tyre to the smaller diameter shoulder, and you reduce the wheelbase further to undermine stability even more.

When “Instinct’s” front suspension system is compressed under braking (or over bumps), the twin-wishbones move through an arc which slightly increases the wheelbase and also helps compensate for the decreasing diameter of the tyres when leant over in a corner. Another safety benefit with the twin-wishbone front end is that it rides over bumps a lot better as there is none of the stiction associated with a conventional telescopic fork, and the inbuilt stability of the system makes it more difficult for large bumps and potholes in the road to unsettle the motorcycle. Duncan is still in the process of getting “Instinct” road registered (mudguards, lights and a speedo are all that’s needed), but has managed to put in some exploratory laps at the Mallala race track, and these have more than confirmed his faith in the design.

Just as impressive though are the secondary safety features of Duncan’s design. From his research, he found that the front end t-bone was one of the most common accidents happening to motorcyclists and that there was a marked increase in the number of injuries to the lower abdominal region of the rider, whom according to the statistics are mainly males under 25. Not good for the family jewels. It was discovered that the increasing size of air boxes on motorcycles to help manufacturers meet noise pollution and performance requirements, were also increasing the height and width of fuel tanks with the aforementioned consequences.

By using an underslung fuel tank on “Instinct”, Duncan was able to go “organic” with the design of the dummy tank and seat unit, allowing it to be made lower in height and narrower in width as it is purely for styling. The next problem our poor crash victim faces once he makes it past the fuel tank are the handlebars. These have a nasty habit of shattering parts of the lower leg, which most definitely is not something to look forward to while holding onto one’s crotch.

Duncan has solved this problem by using shear pins through the steering yoke to lock “Instinct’s” handlebars in place. As the name suggests the pins will shear when hit with a reasonable force, causing the handlebars to pivot forward and away, thereby saving the rider from a more serious leg injury. While we’re on the subject of lower legs, Duncan has also made the foot pegs solid and mounted them at bumper bar height as he believes this offers better protection from errant car drivers than the swivel up type, which are more likely to cause the riders lower leg to be squashed in an accident.

Perhaps more than anything Duncan’s design project highlights how almost laughingly obvious some of the solutions are to the inherent problems built into the traditional motorcycle, and just as equally, how conservative motorcyclists are when it comes to accepting new technology. Ask anyone at Yamaha involved with the GTS 1000. Even the successful BMW R1100RS incorporates a sliding fork un its single wishbone front-end, not only as a necessary part of the design but also, no doubt, so as not to scare away too many traditionalists.

In Duncan’s case, he has taken a step backwards to go forward by basing his design on a simple, reliable, single cylinder engine, and of course, a tubular steel frame to help package his concepts. Although “Instinct” is designed to be built in a kit form, it, unfortunately, is beyond Duncan’s means to manufacture and market the design in any realistic numbers. Let’s just hope there’s a manufacturer out there with enough foresight to prevent such an interesting and practical design becoming more than just another one off special.

Words and photographs Geoff Dawes (c) 1994. Published in Streetbike April/May 1995.