There are few places on planet earth that are as alien in appearance as the desolate surroundings of Bonneville Salt Flats. Situated not far from the Wendover Air Force Base in the State of Utah USA, this extraterrestrial looking terrain, covered by an expansive sheet of grubby white salt and girdled by a jagged brown-black mountain range, became an eerie backdrop for one of the greatest gatherings of outright Land Speed Record contenders the world had ever seen.

Four Americans and their streamlined leviathans assembled on the salt during a cool August in 1960 to try and break Englishman John Cobb’s 1947 record of 634.40kph (394.20mph) which for 13 years had stood unchallenged. In a flurry of national pride, it became the aim of these four very different individuals to recapture the title that was last held by the United States in 1928, when Ray Keech, driving his White Triplex Special, exceeded Captain Malcolm Campbell’s record of 333.063kph (206.956mph) by a mere 0.959kph (0.596mph).

But in 1960 the array of potential record breakers was even more formidable.

Athol Graham, a devout Mormon, had dreamed he would break the Land Speed Record and regarded it as a divine revelation. His “car”, named the City Of Salt Lake, used the aero engine from industrialist Bill Boeings Miss Wahoo unlimited hydroplane and produced more than 2,238kw (3,000hp). Clothed in a channelled ex-Air Force fuel drop tank, the agricultural standard of preparation had led some to consider it a “clunker”. But nonetheless, Graham clocked a surprising 538.76kph (344.761mph) the previous December in the rear wheel drive machine on the Bonneville salt.

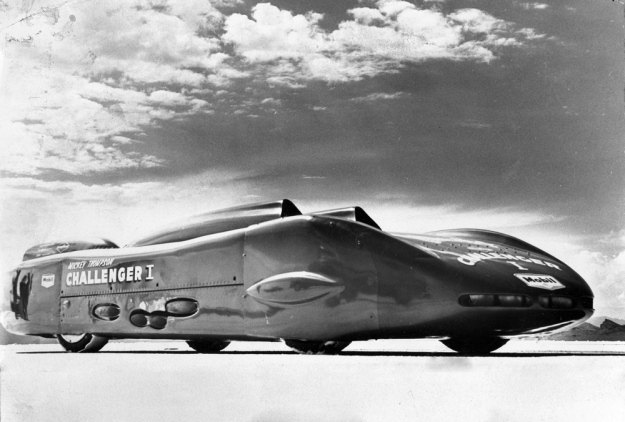

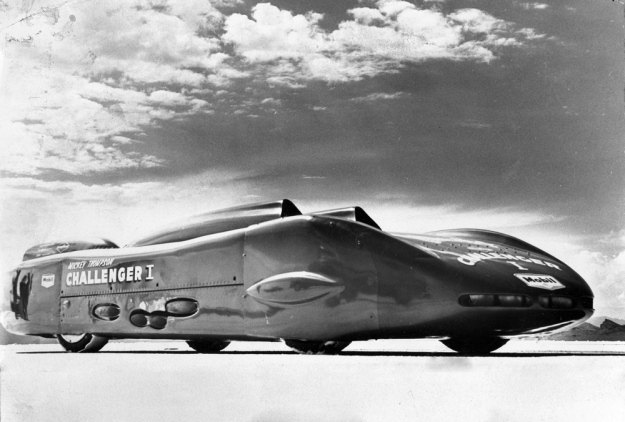

Then there was Mickey Thompson, a product of the American Hot Rod scene and the American National Land Speed Record holder. Thompson was the most experienced of the group and undoubtedly the best prepared with his LSR car Challenger 1. Although on paper it may have seemed an unsophisticated device, using four scrap 6.7litre V8 Pontiac engines, with supercharging it produced over 2088kw (2,800hp). The engines were also ingeniously mounted in pairs and facing each other so the power could be transmitted to both the front and rear wheels through their own individual transmissions and final drive.

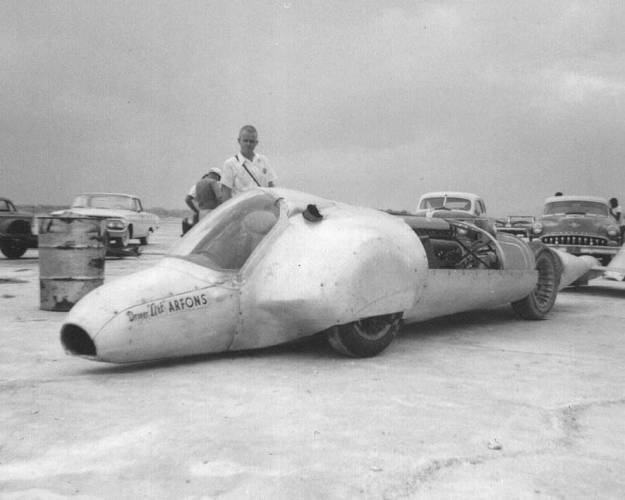

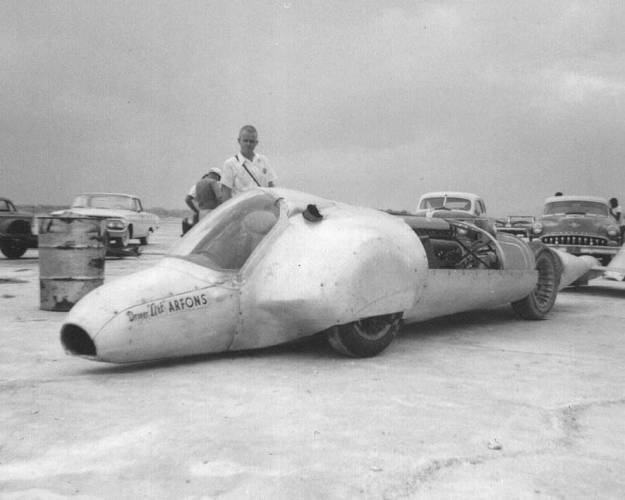

A newcomer to Land Speed Record breaking was the well-known drag racer, Art Arfons, driving number 12 in his series of soon to be famous Green Monsters. Nicknamed “Anteater” due to its long pointed snout, it used a more powerful version of the Allison aero engine than Graham’s, putting out around 2,834kw (3,800hp) in Arfon’s untried rear-engined machine.

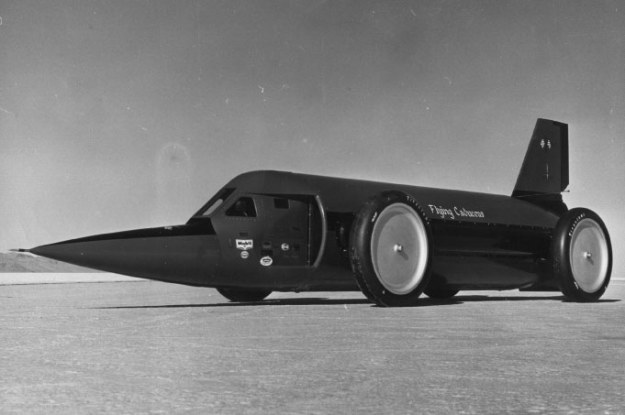

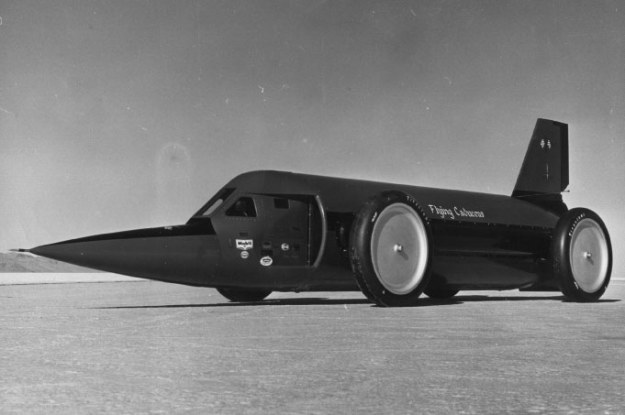

But perhaps the most amazing LSR contender of this gathering was physician Dr Nathan Ostich’s pure thrust jet engined vehicle called Flying Caduceus. Named after the medical emblem taken from Greek mythology, it used a General Electric J47 turbojet from a Boeing B36 bomber, which produced the equivalent of 5,220kw (7,000hp) and was the first of a new breed of jet-engined record contenders. Although it was technically ineligible, according to the world governing body of motorsport, the F.I.A., Ostich was prepared to thumb his nose at the European based governing body to become the fastest man on land.

Dr Nathan Ostich’s Flying Caduceus powered by a pure thrust jet engine.

The scene was now set for one of the great confrontations in Land Speed Record breaking history.

First to venture onto the salt was Athol Graham. Concerned about the prevailing crosswinds and some aspects of Graham’s engineering, the experienced Mickey Thompson talked caution to the Mormon idealist. Off his own back, Thompson had already asked for a telephone pole to be removed at the southern end of the course to reduce any potential risk during Graham’s run. But Graham could not be dissuaded and using full power from the Allison aero engine he rocketed his two-wheel drive vehicle flat out down the salt. The City of Salt Lake was clocking over 482.80kph (300mph) when tragedy struck. The strong crosswinds caused the home built special to yaw off course and snap sideways into a tumble before losing its tail and becoming airborne. With a sickening crunch, City Of Salt Lake landed upside down before rolling over and over. There was little hope for Graham who had not worn a safety harness. Although an inbuilt roll bar had withstood the numerous impacts, the engine firewall had crumpled, protruding into the car and breaking Graham’s spine. He was dead on arrival at Tooele Valley Hospital 177km (110 miles) away.

If this was to be a warning of how treacherous Bonneville could be, it did not work. Five days later 52-year-old Los Angeles physician, Dr Nathan Ostich, took his jet-powered car out on the salt. Designed and engineered by Ray Brock, the publisher of Hot Rod magazine and hot rod doyen Ak Miller, Flying Caduceus had been wind tunnel tested at California Poly Tech, and with 5220kw (7,000hp) on hand, it was calculated to be capable of 804.67kph (500mph). But problems with a porous fuel pump, collapsing air intakes, then severe vibrations and brake and steering problems forced Ostich and his team to eventually withdraw.

Even so, the flying doctor salvaged some pride by reaching over 482.80kph (300mph) during one precarious run.

Art Arfons contender nicknamed “Ant Eater”. It’s clear to see why.

Art Arfons took briefly to the salt with his Allison rear-engined Green Monster, only to have a bearing go in the cars final drive on the return run. Arfons released his breaking parachute, which then promptly snapped its nylon line. Even though his first probe run had reached almost 402.33kph (250mph) with plenty in hand, Arfons acknowledged that “Anteater” was not up to Land Speed Record breaking standard and withdrew.

In the meantime Thompson had been building up speed, making one run at an impressive 569.70kph (354mph). He too had been encountering problems, the suspensionless Challenger 1 suffering from a lack of front wheel adhesion, which was finally solved with some extra ballast and an aerofoil above the nose of the car. Thompson was now ready for some serious runs, but an unexpected downpour had washed away the black guideline and the oil truck re-laying it became bogged in the mud flats. This did not faze Thompson at all, and he elected to run without the guideline, easily managing a one-way speed of 596.67kph (372 mph). Buoyed by this Thompson was ready to go for the record, and with his next run recorded a sizzling speed of 654.35kph (406.60mph). This was faster than Cobb’s best run of 648.783kph (403.135mph), and Thompson knew if he could get a half decent return run through the measured mile then his two-way average would be enough to beat Cobb’s record by the required minimum of one percent. America would, at last, regain the world record.

Challenger 1, Mickey Thompson’s American National Land Speed Record holder.

Regrettably, as so often happens in record-breaking, the return run was an anti-climax with Challenger 1 suffering a broken driveshaft. Thompson did try his luck again, but this time a broken chain driving a supercharger put paid to Mickey’s dream.

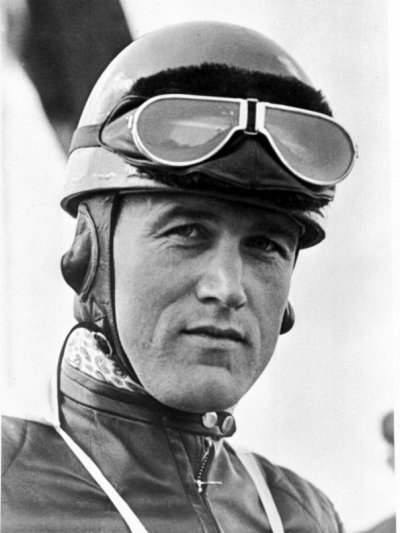

There was, however, one more record contender. Arriving at Bonneville in early September in an attempt to usurp any American record, enigmatic Englishman, Donald Campbell, returned to where his father, Sir Malcolm Campbell, had set a new outright Land Speed Record of 484.620kph (301.129mph) in 1935 to become the first man to break through the 483kph (300mph) barrier.

As a fourteen-year-old boy, Donald had witnessed his father’s triumph. Twenty-five years later and with six World Water Speed Records under his belt, Campbell was challenging for the record his father had held nine times. In keeping with family tradition Donald also named his record-breaking hydroplane and his Land Speed Record contender, “Bluebird”, as his father had, in honour of Maeterlinck’s play, “The Blue Bird”.

Donald Campbell’s Bluebird CN7. British pride and prestige were at stake.

But if the American gang had been imposing, it was Campbell’s entourage that made the hard to impress Americans jaws drop. With nearly a hundred personnel, forty tons of equipment and a convoy of support vehicles, it would have been hard not to gasp at the sheer size of Campbell’s undertaking.

And then there was Bluebird herself. Designed by Ken and Lewis Norris, (who had also been responsible for Campbell’s World Record-breaking hydroplane) Bluebird CN7 had been built by Motor Panels, a subsidiary of Sir Alfred Owen’s Rubery-Owen group, with the support of approximately 80 British companies and at the cost of close to one million pounds sterling. The massive car was powered by a Bristol-Siddeley Proteus gas-turbine engine producing 3,057kw (4,1000hp) at 11,000rpm that powered all four wheels through two David Brown fixed ratio gearboxes. Bluebird was to be a shining example of British technology and engineering at its best, and no expense had been spared in this pursuit.

Unimpressed by the Englishman’s seemingly limitless resources. Thompson played on Campbell’s superstitious nature by telling him how poor the condition of the salt was in an attempt to psyche him out. Arfons too was critical of the fact that Campbell had not driven Bluebird before coming to Bonneville and dryly referred to it as, “on the job training”.

Now it was time for Sir Malcolm’s son to prove himself.

Campbell (left )in discussion with Mickey Thompson (right). Thompson played on Campbell’s surreptitious nature.

Campbell initially made some gentle runs to get accustomed to the monstrous blue car, building up slowly from 200kph (124mph) to 386kph (240mph) before asking for the steering ratio to be lowered after the runs.

Despite still being unhappy with the steering, Campbell went back out to make his fifth run. Bluebird managed to accelerate to 483kph (300mph) within three miles, putting a smile of relief on Campbell’s face. CN7’s designer, Ken Norris, promptly reminded him that the minimum required was two miles if they were to achieve a new record. Campbell then made what would be a fateful decision to do some acceleration tests. Norris was clearly unhappy about this and Dunlop tyres Don Badger also reminded Campbell that the test tyres fitted to CN7 were only good for 483kph (300mph).

On the return run Campbell accelerated the massively powerful car much harder and had reached almost 580kph (360mph), when, in circumstances almost identical to Athol Graham’s accident, Bluebird strayed progressively off course before spinning sideways and rolling over. The massive 4,354kg (9,600lb) car suddenly leapt into the air for what seemed like an eternity before crashing back down onto the salt as it continued to roll over, shedding wheels and bodywork until finally sliding on its belly to a halt.

Campbell somehow survived the worlds fastest automobile accident.

Although sustaining a fractured skull, contusion of the brain, a burst inner ear and various lacerations, Campbell had somehow survived the world’s fastest automobile accident. But the car was a total write-off except for the Proteus gas-turbine engine and some minor ancillary components.

Bonneville Salt Flats and Cobb’s record had not been conquered. But this was to be just a prelude to a new chapter, as Campbell and a rebuilt Bluebird would challenge for the record again in Australia, while Arfons, Ostich and Thompson would try their hand once more at Bonneville. For as different as these men were, they all shared the same dream and possessed the same kind of superhuman courage and determination that is needed to try and become the fastest man on land.

Words Geoff Dawes (C) 2002. Images courtesy http://www.samuelhawley.com, http://www.gregwapling.com, http://www.thompsonlsr.com, http://www.dburnett.photoshelter.com, and http://www.rbracing-rsr.com.