It ‘s an understatement to suggest that racing success helped build the very foundations of the Honda Motor Company. It was the driving force to win, instilled by corporation founder Soichiro Honda that the company’s engineering capabilities be proven in the white heat of competition. The forays, starting in 1959 to the Isle of Man TT, to take on the best in the world in Grand Prix racing, proved pivotal to the success of the fledgeling motorcycle manufacturer.

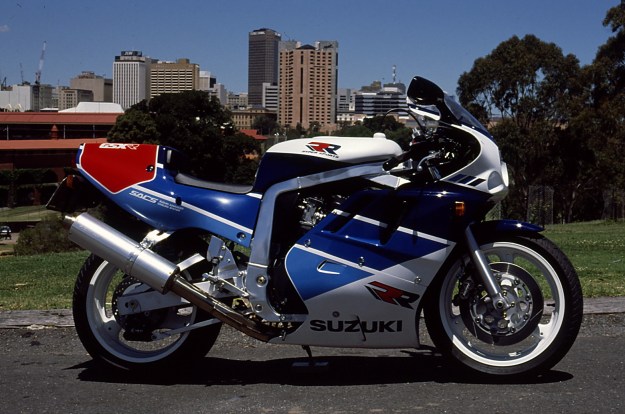

But in 1970’s production racing, and in particular the prestigious Australian Castrol Six Hour production race, this philosophy was faltering. In a class of racing that pitted showroom floor models against each other under racing conditions, Honda had tasted success but once, in the 1971 event, with the venerable CB750.

The Castrol Six-Hour had become the jewel in the crown of endurance production racing that enjoyed live television coverage in Australia and immense media exposure all over the world. It was a class of racing with a huge following as it allowed motorcycle owners to see how “their” bike performed against machines from the other manufacturers. And in an era of unprecedented motorcycle sales, the old adage, “what wins on Sunday sells on Monday”, had never been more true.

Honda held great hope for success in 1979 with the RCB endurance racer inspired CB900FZ, but it was unable to be fully competitive against its larger capacity rivals from Suzuki and Yamaha. Although claiming a creditable third place the previous year, Honda’s own CBX1000 six-cylinder flagship did not have the success that Honda desired.

And the war for production racing supremacy was not just being waged in Australia, but also South Africa, New Zealand and the U.K which was also a part of Honda’s dilemma. This required contemplation and a new approach to the race, or rather, the regulations.

The CB1100R series of motorcycles was created out of production racing necessity. Honda became the first Japanese manufacturer to build a production homologation special for the road, manufacturing enough road-registerable models to stay within the rules.

In a clever bit of reverse engineering Honda looked to its CB900FZ road bike, which had been based on the highly successful RCB1000 endurance racer. It used lessons learnt from the RCB to transform the CB900F into a specialist endurance production racer. There was some irony here as Honda was also developing in parallel the RSC1000, by necessity based on the CB900F, to meet the regulations for the new prototype World Endurance Championship of 1980.

Honda Australia rider Dennis Neil was recruited by Honda Japan to develop the new machine and was responsible for testing it in both Australia and Japan. One hundred of the CB1100RB were fast-tracked and registered by Honda to make the September cut off deadline for entry into the 1980 Castrol Six Hour. This was an unfaired version of the bike, which was unique to the R series. European models and those released in most other markets were fitted with a half fairing.

The evolution of the CB900F to transform it into the CB1100R, though, was quite extensive.

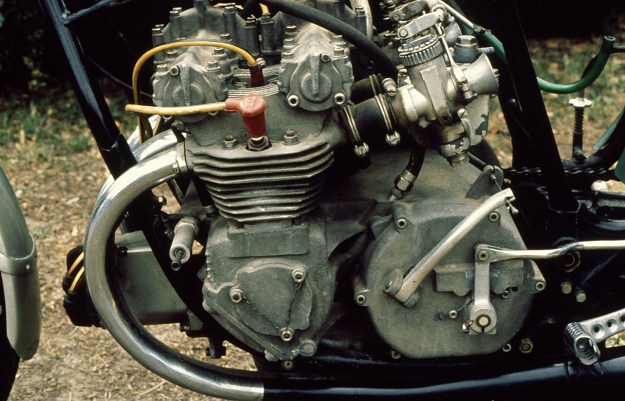

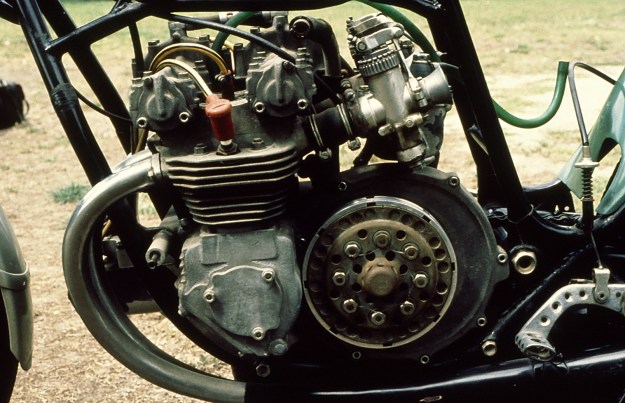

Although the engine shared the same 69mm stroke of the CB900F, the bore was increased from 64.5mm to 70mm to give an engine capacity of 1062cc, the same as variants of both the RCB and RSC endurance racers. The cylinder block was solid, doing away with the air gap between the two outer and two inside cylinders. The compression ratio was increased, up from 8.8:1 to 10:1, and many of the engine internals were beefed up, including a wider primary drive chain, strengthened clutch, conrods, big end bearings and gudgeon pins while the pistons became semi-forged items and the camshafts had sportier profiles. The standard gearbox was retained, although final overall gearing was raised by ten percent, and carburation also remained the same as the CB900F using four constant velocity Keihin VB 32mm units. This resulted in CB1100RB producing 115hp (85kw) at 9000rpm and 72ft.lb (98N-m) of torque at 7,500rpm, compared to 95hp (69.8kw) at 9000rpm and 57ft.lb (77.4N-m) at 8000rpm of the CB900FZ.

The chassis was strengthened with extra gusseting and the detachable lower frame rail of the CB900F, designed for ease of engine removal, now became a solid part of the frame. The front engine mounts were also heavy-duty alloy items, which no doubt all helped to improve the rigidity of the chassis. The 35mm CB900F front forks were replaced with new 38mm units that used air assistance to adjust the spring rate via a linked hose from each fork and the rear shock absorbers carried a finned piggyback reservoir to help cool the damping oil. Honda reverse Comstar wheels were fitted although the diameters remained the same as the CB900F, with an 18inch rear wheel and a 19inch front. But the rim widths were wider, up from 2.15 inches for both the front and rear of CB900F to a 2.75 inch rear and a 2.5 inch front for the CB1100RB. This was to accommodate the new generation tyres developed for the race due to the intense competition between tyre manufacturers. Honda also introduced for the first time their dual twin-piston floating calipers that gripped solid 296mm disks.

A single fibreglass seat unit that also housed the toolkit took the place of the CB900F’s dual seat. The fuel capacity was increased from 20 litres to 26 litres with a massive alloy fuel tank. The instruments and switchgear were taken straight off the CB900F, but the duralumin handlebars were changed to multi-adjustable items that could be replaced quickly in the event of a crash. The exhaust system was visually similar to the CB900F, being a four into two, but on the CB1100RB it was freer flowing and utilised a balance pipe just ahead of the two mufflers. It was also finished in matt black as opposed to chrome and was well tucked in. The pulse generator and ignition cover on either end of the crankshaft were reduced in size and chamfered to also help improve ground clearance. The foot pegs were rear-set and raised slightly on new lighter alloy castings. Honda was quite proud of achieving a fifty-degree angle of lean for the RB without anything touching down. This was extremely important at such a tight circuit as Amaroo Park where the Castrol Six Hour was held.

However, the Willoughby District Motorcycle Club did not welcome the appearance of the CB1100RB at the 1980 Castrol Six Hour. The organisers of the event argued that the CB100RB did not conform to the rules for a touring motorcycle, as it had no provision to carry a pillion passenger. Honda quite rightly pointed out that this was not written into the supplementary regulations for the event and indeed the organisers had to yield. It should also be pointed out that the organisers had turned a blind eye in previous years to entries such as the 750 and 900 SS Ducati’s that also could not carry a pillion passenger.

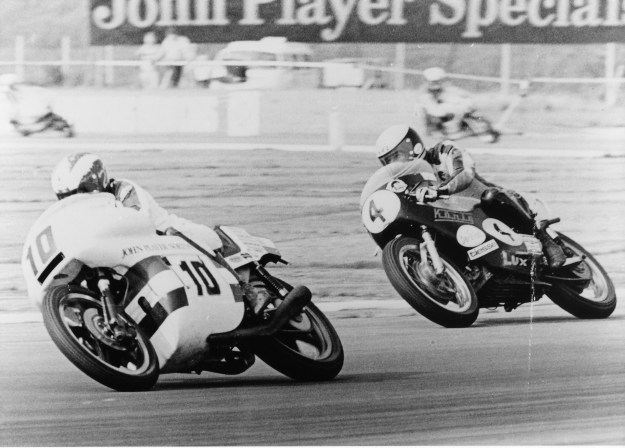

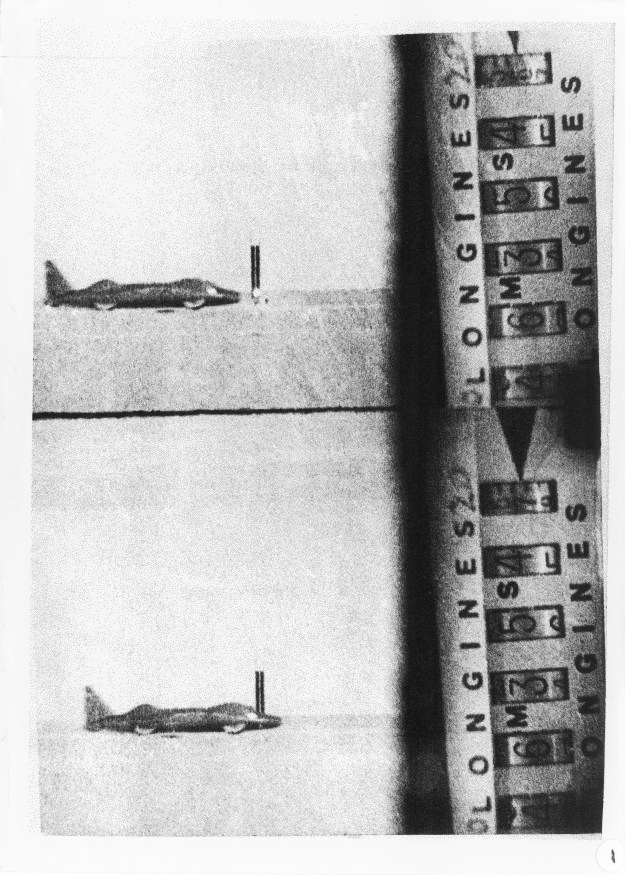

It’s history now that Wayne Gardner and Andrew Johnson on the privately entered Mentor Motorcycles CB1100RB won the race, held in wet conditions, ahead of the Honda Australia entry of Dennis Neil and Roger Heyes. But it was a controversial win and not the clear-cut victory Honda would have hoped for. Suzuki Australia claimed that a lap scoring error had taken the win away from John Pace and Neil Chivas on a GSX1100. After three appeals the Suzuki team were eventually awarded the win, only for Mentor Motorcycles to appeal against the ruling and be reinstated just four weeks before the 1981 race. To top all this off, the WDMC released the supplementary regulations for the race, which specifically banned solo seats. Honda turned its back on the 1981 race and once again studied the rules. Some solace was sought when the CB1100RB won all of the eight 1981 MCN Streetbike series in the UK, with seven victories going to series winner Ron Haslam.

The end result of all of the above culminated in the 1982 CB1100RC, which came equipped with a dual seat and rear footpegs – and also a full fairing. A removable cover was used to give the appearance of a single seat, while the tools were moved to a lockable toolbox that was hung off the seat subframe just behind the left rear shock absorber. The rear suspension units were now inverted reservoir gas charged FVQ units with four-way compression damping and three-way adjustable extension damping with five spring preloads. Front fork diameter was increased from 38mm to 39mm with separate air adjustment on the top of each fork leg. The forks also boasted a new innovation from Honda, Torque Reactive Anti-dive Control or TRAC. This was a mechanical four-way adjustable system that utilised the pivoting torque of the brake calipers to close a valve in the fork leg, under braking, to increase compression damping which limited front end nose-dive.

The front brake disks now became ventilated while 18-inch “boomerang” spoked Comstar wheels graced both ends of the RC. The rear rim width was now 3.0 inches, up from 2.75 on the RB, while the front rim width remained 2.5 inches but on an 18 instead of 19-inch wheel. Steering rake was increased by half a degree to 28 degrees and trail was shortened from 121mm to 113mm mainly to accommodate the effects of the new 18-inch front wheel. The wheelbase also became slightly longer from 1488mm of the RB to 1490mm for the RC but still 25mm shorter than the CB900F.

The instrument “pod” now was now mounted in the nose of the full fairing, and the tachometer became electronic as opposed to the cable driven item of the RB. There was also the inclusion of an oil temperature gauge mounted with the warning lights on the top steering yoke. The full fairing was lightweight fibreglass, reinforced with carbon fibre, and its lower half was quickly removable utilising six Dzus type fasteners and two screws. In the engine department, the only significant mechanical change was a stronger cam chain tensioner and 1mm larger Keihin VB 33mm CV carburettors. Claimed horsepower and torque remained the same as the CB1100RB, although South African and New Zealand models were recorded as giving 120hp.

Honda dominated the 1982 Castrol Six Hour even though Suzuki unleashed its 1100 Katana with special wider wire wheels. Wayne Gardner and Wayne Clarke took the top place on the podium with three other CB1100RC’s finishing behind them. The nearest Suzuki Katana was a lap down in fifth. Honda again dominated the British MCN Streetbike series winning all the races with Ron Haslam and Wayne Gardner sharing the spoils and series title. For 1983 new restrictions were put in place for production racing, which limited engine capacity to 1000cc and effectively made the CB1100RC redundant.

Honda still produced one more model in the series, the 1983 CB1100RD, the main differences from the RC being a rectangular tube swingarm, which was slightly wider for the new fatter tyres, and it also carried upgraded rear shock absorbers. The nose of the fairing was also pulled back to be in line with the front axle to meet racing regulations. Aesthetically the blue stripe ran up the sides of the headlight and not underneath it while the blue and red paintwork appeared almost metallic in its finish. The Honda winged transfer on the tank was grey, black and white as opposed to yellow and white of the RB and RC.

The overall finish of the RD appeared a notch above the RB and RC, and it was suggested that Honda did not have the capacity on its production line to cope with the limited number run required to homologate these two models. Honda’s Racing Services Centre (which became the Honda Racing Corporation in 1982) was said to have been responsible for assembling both the RB and RC. An upgraded production line in 1983 enabled Honda to accommodate the RD. This does make sense and a good reason for the better quality of finish of the RD. It also makes the RB and RC somewhat unique as they would have been assembled by Honda’s racing department.

How limited in numbers was the CB1100R series? 1,050 of the 1981 RB were reported to have been built, although whether this figure includes the 100 fast -racked unfaired machines for the 1980 Castrol Six Hour is unclear. It seems that 1,500 of both the RC and RD were made, giving a number of 4,050 in total.

Words Geoff Dawes © 2013. Photographs Geoff Dawes (C)1982. Images http://www.nirvanamotorcycles.com, http://www.mctrader.com.au, http://www.worldhonda.com, http://www.carandclassic.co.uk, http://www.flkr.com.